When I began writing about horror cinema as a form of oblique artistic grappling with our real-life treatment of nonhuman animals, it was with enthusiasm and several convictions. First, that this approach would merge two of my primary interests, philosophical issues of animal rights and their aesthetic representation and also scary movies.

rick

Things are not quite what they appear to be in Surname Viet Given Name Nam, Trinh T. Minh-ha’s masterful 1989 documentary.

Beginning as an apparently straightforward portrait of several women’s lives in past and present Vietnam, the film grows increasingly experimental as it continues, morphing into a feminist, post-colonial interrogation of form, positionality, the authority of the image, and film ethnography itself.

Last month, we took a look at the curiously crucifixion-focused, cyborg-lacking endeavor Cyborg, featuring Jean-Claude Van Damme and the leftover costumes from Cannon Films’ abortive attempts to make Spiderman and a Masters of the Universe sequel. As I noted at the time:

Cyborg is fascinating for a number of reasons, but the connection between its eroticism and death fetish is its most notable.

Winner of the 2015 Golden Lion in Venice, Lorenzo Vigas’ From Afar (Desde allá) is the slowest of slow burns. A story of distance, proximity, and perspective, it teases out the hidden meanings behind character surfaces in ways that either prove thrilling or excruciating, depending on your tolerance for long stretches of silence and similar arthouse trappings.

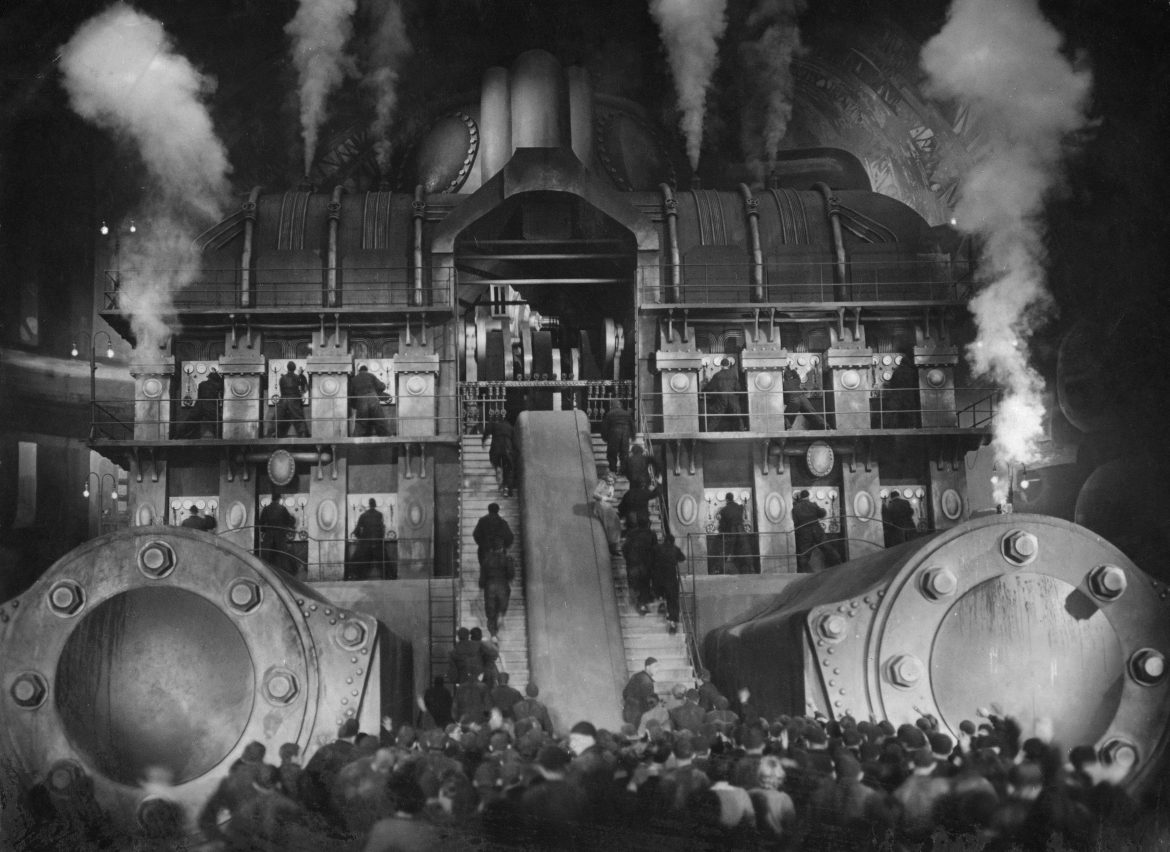

Metropolis is indisputably one of the most celebrated films of the Silent Era and the generally agreed-upon cinematic pinnacle of Weimar. A dystopian sci-fi landmark distinguished by incredible set design and in-camera tricks, director Fritz Lang’s monumental ode to “the heart” as the “mediator of head and hands” was hugely influential on dozens and dozens of films to follow.

In an online film community of which we are both members, my pal Liz Lerner suggested a novel and fascinating idea. For the entire month of September, we are watching and considering films from a specific, arbitrarily chosen year, attempting to locate their concerns, aesthetics, and quirks in the material conditions of their creation and examining what they might have to say to each other.

Happy Labor Day!

You know, the day in early September that Grover Cleveland declared a federal holiday as a halfhearted apology for his troops murdering several workers during the Pullman Strike in 1894, a desperate, election-year attempt to stave off radical reform while also conveniently distancing the U.S.

The original Jaws is a stone-cold classic. Its director, some guy named Steven Spielberg who probably has a promising career ahead of him, expertly paced the original summer blockbuster, drew nuanced performances from Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, and Robert Shaw, and had the good sense to show as little of the titular shark as possible, allowing dread to build and imaginations to run wild.

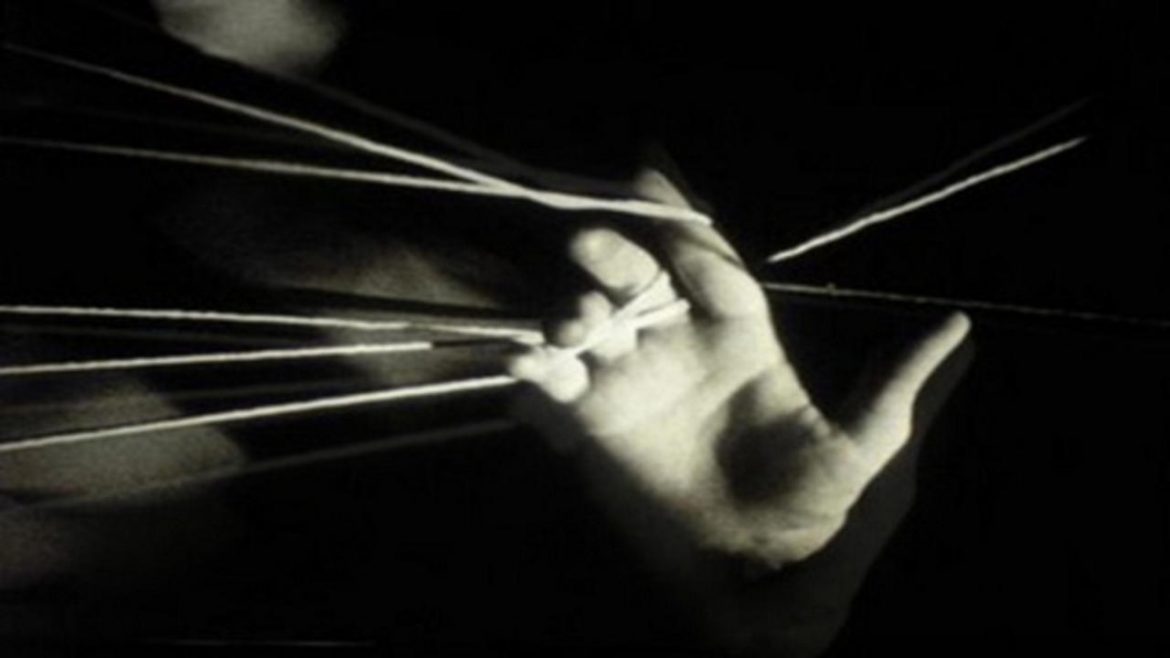

The works of Maya Deren are hugely influential touchstones for experimental cinema, frequently cited and studied. Her luminous debut Meshes of the Afternoon, covered here as part of the Counter-Programming The Great Movies series, is a widely recognized classic of the form, a dreamlike visual interrogation that, in Deren’s words, “externalizes an inner world to the point where it is confounded with the external world.”