The Love Witch is a two-hour MASH-note to bygone genre films, with the blindingly bright color palette of a late 60s cheapie and the stilted dialog to go with it. For producer/director/writer/editor/set and production and costume designer/non-harp-playing harp-music composer Anna Biller, it’s clearly a labor of love: there’s a handmade quality to every aspect of The Love Witch‘s pulp-horror stylings, and a witty, feminist self-awareness.

rick

Sieranevada is a chronicle of false starts and interruptions. Clocking in at nearly three hours and rarely venturing out of a single, cramped apartment, writer/director Cristi Puiu‘s ultra-realist epic of Romanian family dysfunction is simultaneously hilarious and insufferable, filled with complicated interpersonal back-stories, old grudges, and meals that can’t seem to get started.

Lee Morgan was only a teenager when he exploded onto the bop scene, a cocky but undeniably talented kid ably sharing the stage with Dizzy Gillespie. He played alongside his friend Wayne Shorter in Art Blakey’s legendary Jazz Messengers, basically defining Blue Note’s hard bop sound at the time.

When The Lost City of Z was screened earlier this week at the San Francisco International Film Festival, director James Gray took to the stage to briefly introduce it.

After some kind words about our fair city and an enthusiastic celebration of the communal theater experience he holds so dear, Gray closed it out by saying:

Well, that’s probably enough.

Brillante Mendoza‘s films, social realist to the core, tend to focus on marginalized people in Manila struggling to get by in gritty circumstances. The prolific Filipino auteur (24 credits in 11 years) won the Best Director award at Cannes for his Kinatay, and the electrifying Ma’ Rosa continues in a similar thematic vein.

Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne specialize in humanist fables, small-scale social realist portraits of working-class people caught in difficult moral situations. At their best — the Palme D’or-winning L’Enfant, The Kid With A Bike, Two Days, One Night — the brothers conjure believably fraught circumstances and ethically conflicted characters on journeys of different kinds.

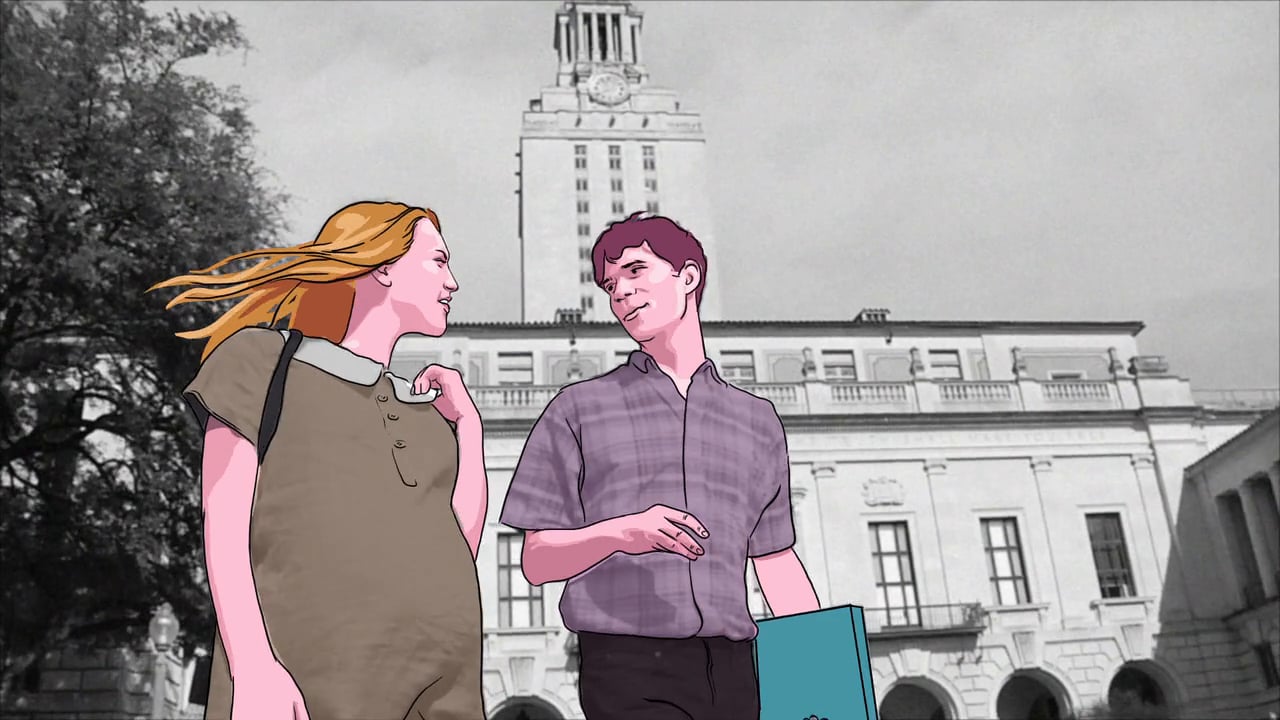

On a blisteringly hot August day in 1966, Charles Whitman — a former Marine who’d killed his wife and mother the night before — climbed the the Main Building tower at the University of Texas with an arsenal of weapons and started shooting.

There is no moment in Shin Sang-ok‘s A Flower In Hell in which the American post-war occupation of Korea is absent. It is the film’s focal point, even when the soldiers aren’t on screen. Even when lovers are rolling around in the grass.

The three-part Netflix documentary Five Came Back, scripted by Mark Harris (on whose book it is based) and directed by Laurent Bouzereau, is a substantial achievement of narrative compression and historical context.

Focused on the wartime cinematic contributions of five acclaimed directors — Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens, and William Wyler — Harris and Bouzereau examine the nature of filmic propaganda through the lens of individual personalities and creative pressures, seeking to balance a huge amount of information with the needs of the documentary form.

As explained at the start of actual March Madness last month, we have embarked on our 2nd Annual Sports Movie competition for the crown, timed to coincide with the basketball extravaganza that wraps up tonight. And as expected, we are running behind.