There are all sorts of divides between us and the early silent days of Hollywood: assumptions about gender and race; the differences in our ability to fill in what is unsaid (to put back in the implicit sex they had to leave out, for instance); and even the ability to perform the simple act of holding an actor’s face in mind for the seconds until the title card comes up, then retroactively making the face make sense with the words.

Lark

There are certain rich veins of cinematic tradition that we as film writers find hard to tap into. The perfect filmic tradition for critics is one that has enough coherence that readers are interested in reading new articles about it, but enough uniqueness to each film that we can justify writing about them separately.

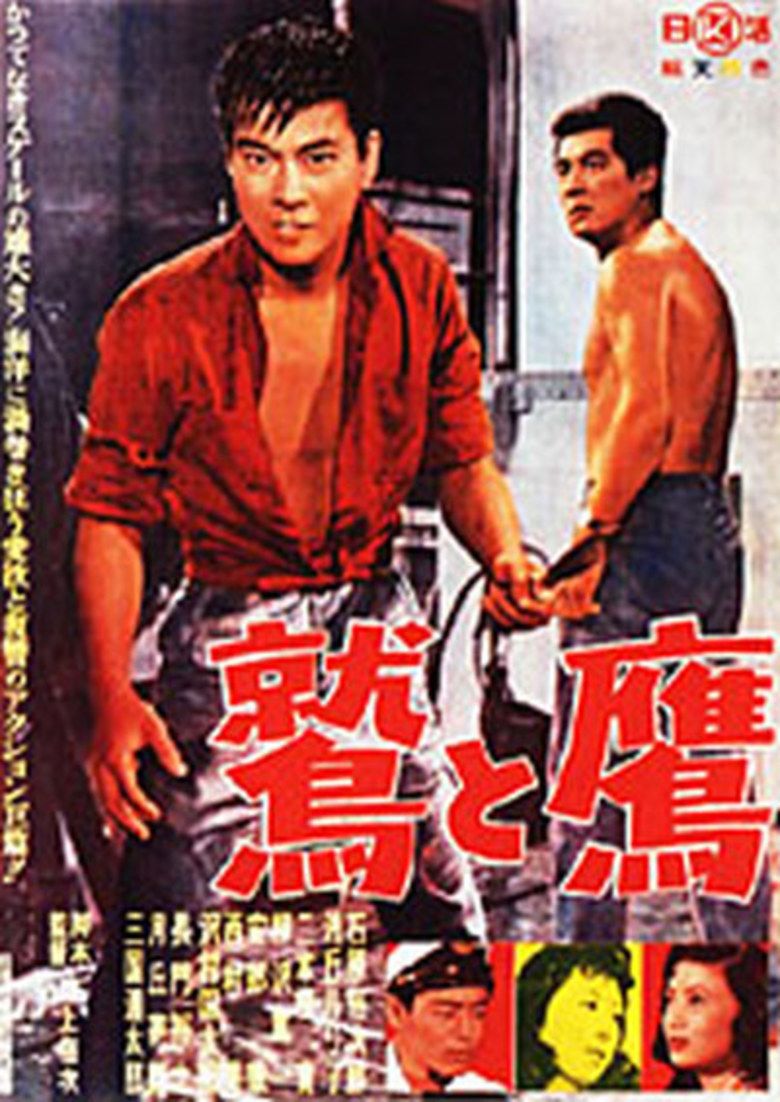

I can’t confirm for sure that the minds behind The Eagle and the Hawk (Washi to Taka, 1957) saw John Ford’s The Long Voyage Home (1940) — a number of shots seem to duplicate ones from the earlier film, although on a ship the number of places from and at which to shoot is certainly delimitable — but I couldn’t stop thinking of the two films next to one another.

Late in The Post, we have the scene, mandated by genre, in which Meryl Streep, trying to make the ethically right decision, talks to her daughter about a memory of the daughter’s childhood — the place in which the daughter, who has been vaguely rebellious, tells her to do what she thinks is right.

The city symphony, as a “genre” (can something so short-lived be a genre?), has the misfortune of being mostly associated with a particularly unrepresentative entry: Dziga Vertov’s justly famous The Man with the Movie Camera.

Vertov’s movie is still incredible, and deserves its place in every film history class’ syllabus.

We can plot the Great Movies You’re Supposed To Have Seen Canon on a grid, something like the omnipresent Political Compass. One axis is fast vs slow, and the other is positivity-oriented and optimistic vs. mopey depress-os.

A lot of the mutual lack of understanding that sometimes happens when I talk to my fellow film dorks online comes from the oddities of my personal artistic history that have left me to mostly enjoy the slow depress-o corner of the canon map, that corner which has become for many people about as pleasant a place to visit as the dentist’s.

If Monty Python’s “Summarize Proust Competition” had been real, it would be a cakewalk (“A man reminisces a lot, goes to a party, and decides to write the book you’re reading”). A far harder version would take aim at a much shorter book: Chandler’s The Big Sleep.

I distinctly remember being in ninth grade, trying to convince friends to make a movie with me. The pitch: the opening scene of the film was interrupted by the lead actor being hit by a car; as the serious narrative went on, the film kept being interrupted by worse and worse accidents, by more and more actors leaving, until the last scenes were filmed by the director alone in his bathroom, depicting the action with dolls.

It’s probably pointless to try to write a review of Infinity War. [Don’t worry, no spoilers.]

It’s certainly pointless in the traditional way, as a verdict: two and a half stars, B-plus, 72 percent, thumbs up. It’s pointless to talk about the lighting or the editing, the performances or the sound design.

Certain genres, subgenres, movements, categories of art have threatened to purify themselves, if not into silence entirely, at least so far out of the artistic mainstream that it becomes something wholly inward, communicating only with itself.

There are two types of genres that risk such a fate: the most avant-garde and the most lowbrow.