Cinema, according to Nicolas Winding Refn, is “generally not an art form anymore.” Too extreme, or not extreme enough? It is “dead … [and] clings on to our feet as we move forward.”

Film’s physicality is one aspect of Refn’s gleeful proclamations of doom. We simply live in a post-film world, with the hoary conventions, technical challenges, and byzantine structures of ownership and distribution seeming with each passing day to belong to another time and place. To the degree that film exhibition and actual film itself are considered constitutive of “cinema,” the proper place for it now is the museum, where lithographs and daguerreotype live. The enthusiasm for it is the collector’s passion or the scholar’s; “cinephilia” is a rarefied structure of feeling and unlikely to go away anymore than opera has gone away, but marginal and with more than a whiff of fetish. Everyone else is on their phone. (Including, I could add as someone who currently works at a movie theater, in the movie theater.)

David Lynch may rail against the cell phone as an affront to artistry, but Refn is matter of fact: “The only thing to know is that the cinema screen and the phone are co-existent. One is not better than the other. They are co-existent.” This embrace is not so unusual, particularly if we interpret “the cell phone” as a stand-in for digital more generally. This is especially evident among those most indebted to or admiring of the film auteur tradition: Godard‘s late-period embrace of digital is legendary (his Skype press conference for The Image Book being only a particularly puckish recent exclamation point), for instance, and recently Paul Schrader, whose First Reformed reveled in appallingly banal digital surfaces, has taken to social media to declare cinema itself “a questionable term … Cat videos or Shoah? What’s the difference?”

We could chalk this up to good old-fashioned curmudgeonism, a weird variant by which Old Man Yells At Cloud becomes Old Man Extols Cloud. (“In a digital world,” Refn proclaims, like an anarchist philosopher-king, “‘free’ is a currency.”) But the auteurism itself of these spokespeople for Cinema’s Death underscores another point: it’s precisely the possibilities of streaming and the non-hierarchy adherent to digital production that excites, that makes possible new and fresh personal expressions. From this vantage point, it’s not so unlike the ways in which hand-held film cameras and low-budget productions gave birth to the nouvelle vague and, later, independent American film in the good old days of cinephilic worship.

The more curious tension is between the celebration of digital possibility and the archival impulse. It seems it’s those who most fervently declare cinema dead again who also rush to its preservation. The Image Book, like the magisterial Histoire(s) du cinéma before it and from which it draws its method and aesthetic, can be read as a digital processing of the analog memory. First Reformed is in conversation not only with Bresson, Dreyer, and the “transcendental style” Schrader has written about extensively, but with the very flat surfaces of our digital Anthropocene that either give way to despair or provide glimpses of grace. Refn, of all people, simply started buying old films.

The result — byNWR, a free online portal to some of his acquisitions — is as strange as the ironies that underwrite it. Why restore forgotten exploitation movies, no-budget curios, apocalyptic “gospel grindhouse” fragments of anti-Communism if cinema is dead? Why show this digital archive of half-forgotten marginalia, as Refn recently did, in the decidedly analog, decidedly high-fashion space of Fondazione Prada? (“Prada stands for – progression,” Refn offers, unhelpfully.) Why these weird movies, and not others? Why any at all?

The result — byNWR, a free online portal to some of his acquisitions — is as strange as the ironies that underwrite it. Why restore forgotten exploitation movies, no-budget curios, apocalyptic “gospel grindhouse” fragments of anti-Communism if cinema is dead? Why show this digital archive of half-forgotten marginalia, as Refn recently did, in the decidedly analog, decidedly high-fashion space of Fondazione Prada? (“Prada stands for – progression,” Refn offers, unhelpfully.) Why these weird movies, and not others? Why any at all?

To Refn, they are “individual expressions,” unbound by our current aesthetic malaise in which “everything is so generalised and democratic and everyone’s opinion has to be valued, everyone’s department has to be heard, everyone’s idea of acceptability is thought out.” Auteurs, as they say, gonna auteur. The choices are indeed singular, and might even shed light on Refn’s own maximalist provocations. (Watching them, you may find yourself, as I have, appreciating Refn’s work more than before.)

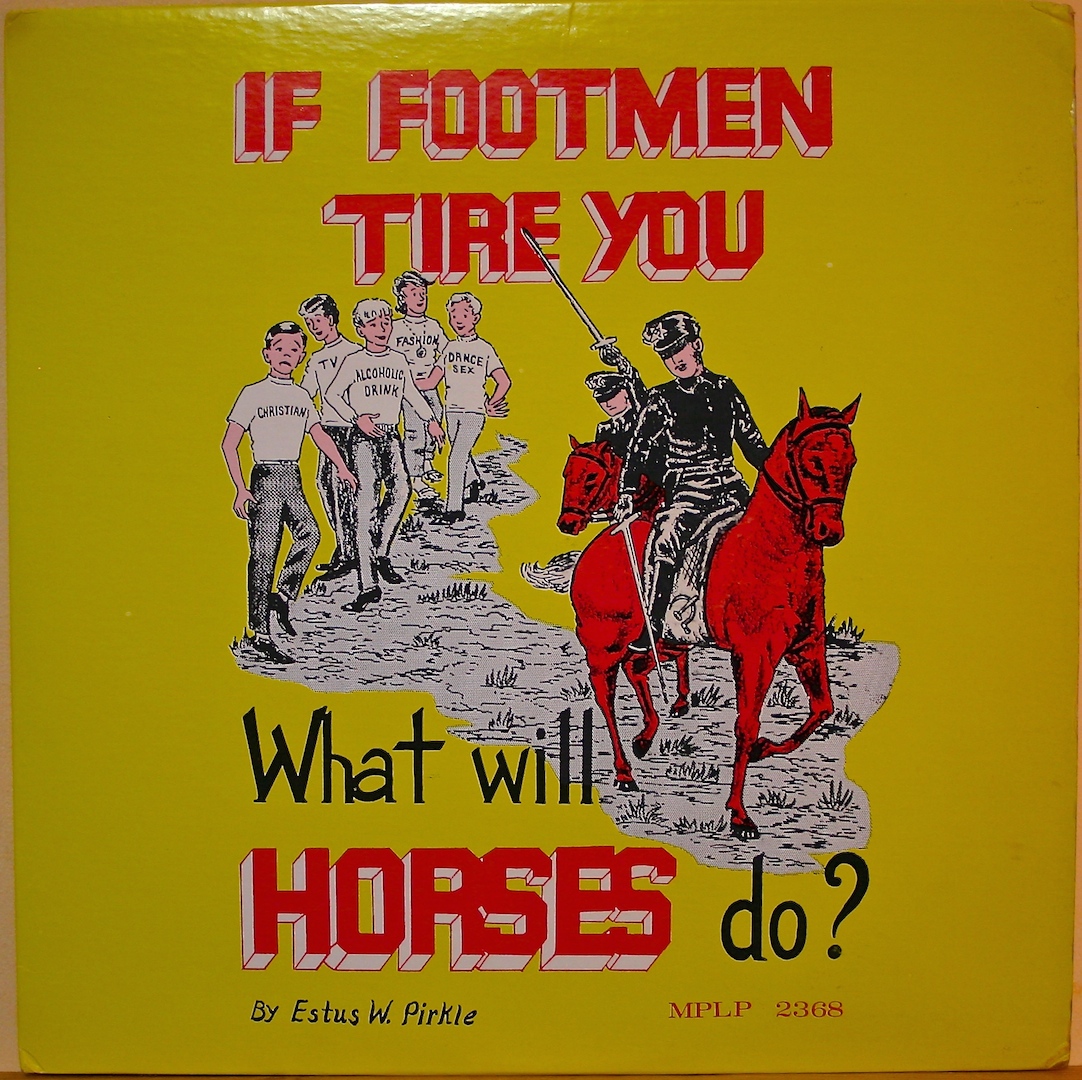

Here are a few favorites from this archive of the undead. The monthly releases are presented as chapters in volumes, each curated by a guest editor: “Regional Renegades,” with stand-out Nest of the Cuckoo Birds, a truly strange swamp Gothic that looks like a broke-ass Night of the Hunter, seems to forget where it’s going, and builds to something delirious. “Missing Links” – which “sheds light on the weird cultural enclaves of American society during the mad mid part of the 20th century” – contains the truly batshit evangelical anti-Communist screed If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do?, almost certainly the only movie you’ve ever seen in which a Soviet officer who wants to replace Jesus with Fidel Castro shoves pencils into a child’s ears so he can’t hear the word of the Lord. “Hillbillies, Hustlers, and Fallen Idols” is “a beguiling selection of stories about those who instinctively mingle their creativity with criminality, habitually push the boundaries of common sense and good taste, and seem to thrive on a chaos of their own making.” Mention must be made of House on Bare Mountain, which pairs (kind of adorable) nudie-cutie prurience with a plot involving a school for girls that serves as a cover for a moonshining operation staffed by a werewolf. But my personal favorite is Wild Guitar, in which Arch Hall, Jr. is your low-rent Elvis and Arch Hall, Sr. your discount Colonel Tom Parker. (Yes, the team behind Eegah! bring you a rags-to-riches rock n’ roll fantasy, a world where nothing looks quite right but is also partially shot, with inappropriate beauty, by Vilmos Zsigmond.)

Here are a few favorites from this archive of the undead. The monthly releases are presented as chapters in volumes, each curated by a guest editor: “Regional Renegades,” with stand-out Nest of the Cuckoo Birds, a truly strange swamp Gothic that looks like a broke-ass Night of the Hunter, seems to forget where it’s going, and builds to something delirious. “Missing Links” – which “sheds light on the weird cultural enclaves of American society during the mad mid part of the 20th century” – contains the truly batshit evangelical anti-Communist screed If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do?, almost certainly the only movie you’ve ever seen in which a Soviet officer who wants to replace Jesus with Fidel Castro shoves pencils into a child’s ears so he can’t hear the word of the Lord. “Hillbillies, Hustlers, and Fallen Idols” is “a beguiling selection of stories about those who instinctively mingle their creativity with criminality, habitually push the boundaries of common sense and good taste, and seem to thrive on a chaos of their own making.” Mention must be made of House on Bare Mountain, which pairs (kind of adorable) nudie-cutie prurience with a plot involving a school for girls that serves as a cover for a moonshining operation staffed by a werewolf. But my personal favorite is Wild Guitar, in which Arch Hall, Jr. is your low-rent Elvis and Arch Hall, Sr. your discount Colonel Tom Parker. (Yes, the team behind Eegah! bring you a rags-to-riches rock n’ roll fantasy, a world where nothing looks quite right but is also partially shot, with inappropriate beauty, by Vilmos Zsigmond.)

The fourth volume, “Smell of Female” (from a song by The Cramps, natch), was just released; its first entry is Chained Girls, an fake-ethnographic sexploitation fantasia of lesbianism that is both hilarious and repellent, sometimes simultaneously. Guest editor Ben Cobb wisely decided to hand over the copious commentary on this volume to “all-girl gang of writers, designers, photographers, artists, editors, musicians and thinkers;” the result aims to be an interrogating and artistic dialog with the archival material.

The fourth volume, “Smell of Female” (from a song by The Cramps, natch), was just released; its first entry is Chained Girls, an fake-ethnographic sexploitation fantasia of lesbianism that is both hilarious and repellent, sometimes simultaneously. Guest editor Ben Cobb wisely decided to hand over the copious commentary on this volume to “all-girl gang of writers, designers, photographers, artists, editors, musicians and thinkers;” the result aims to be an interrogating and artistic dialog with the archival material.

All of which is to say, Refn and his accomplices are up to something truly missing from the vast, flat expanses of streaming: curation, and supplements that go beyond the cursory. Some of the swirling discourse is as idiosyncratic as the films on offer. Did Cuckoo Birds really need a barely related, if fascinating, expose on Florida murder families? Did the John Waters-esque camp of Hot Thrills and Warm Chills warrant an entire biography of its country-music impresario of a director Dale Berry, including links to his non-hits “Varmints In My Garments” and “There’s A Map Of Texas On My Heart”? Did Curtis Harrington’s wonderfully bizarre Night Tide – starring an impossibly boyish Dennis Hopper as a sailor on leave falling in love with a carnie who might be a killer mermaid – obviously call out for a gorgeously constructed rumination on growing up in the shadow of the H-Bomb?

Of course not, but these are the kind of obsessive unearthings and adjacent exorcisms that archival endeavors make possible. If cinema is dead, as Refn insists, then this whole project is a curious half-light séance, an invocation of hauntologies, and a map of non-places. It might be better to consider cinema’s shadow-play as ghostly from the start, and these the strange bursts from vanishing peripheries. Maybe we’ve always been the afterlife.

.