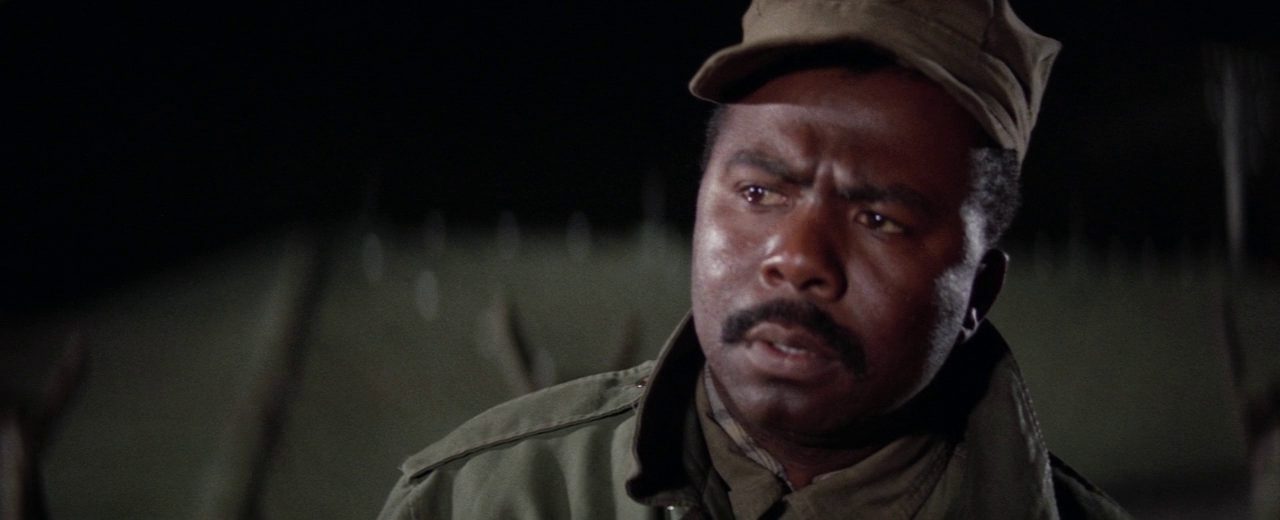

“We aren’t in some American TV show. We don’t need any private detectives,” a policeman tells Joe Shishido (the chipmunk-cheeked tough guy from Branded to Kill and A Colt Is My Passport) early in Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! He’s not quite right: they are actually in a Japanese movie, but one almost perfectly modeled on American TV.

Here there are very few of the traits that would characterize Seijun Suzuki’s late career insanity and that would get him fired from Nikkatsu. Like Dorothy Vallens’ apartment in Blue Velvet, there’s only one place in the film lit with Suzuki’s to-be-iconic color washes; instead, most of the style comes from the ludicrously elaborate suits everyone is required to wear.

At its core, this is a Red Harvest-style “get hired by one gang and play them against another gang to destroy them both” plot. Ironically, Suzuki would release another version of the same plot, Youth of the Beast, in the same year (1963).

At its core, this is a Red Harvest-style “get hired by one gang and play them against another gang to destroy them both” plot. Ironically, Suzuki would release another version of the same plot, Youth of the Beast, in the same year (1963).

But where Youth is a grim story of revenge, Go to Hell is lighthearted series-fodder. We are no more surprised when Joe Shishido makes it through to the end OK than when Joe Friday does. The extended cast is a little too big and too well-fleshed out not to themselves feel like they are borrowed from a longer, more established series (especially his expert-in-blackmail assistant, who is for me a style icon).

What we end up with is not necessarily what people might expect from the legend of Suzuki. The plot is coherent and the action easily followed; there is a traditional love story involving a gangster’s moll that ends with her going straight and driving off with Joe into the sunset (for vacation, of course – he has to be back for the sequel).

But on top of being tremendously fun on its own, Go to Hell reveals how much more Suzuki is than just a shocking weirdo who made a couple weird movies and one very weird one (if you haven’t seen Branded to Kill, you’re in for a ride). He was much cleverer than that, taking American influences and taking them to their furthest possible point in the way only a non-native speaker of a genre-language can.