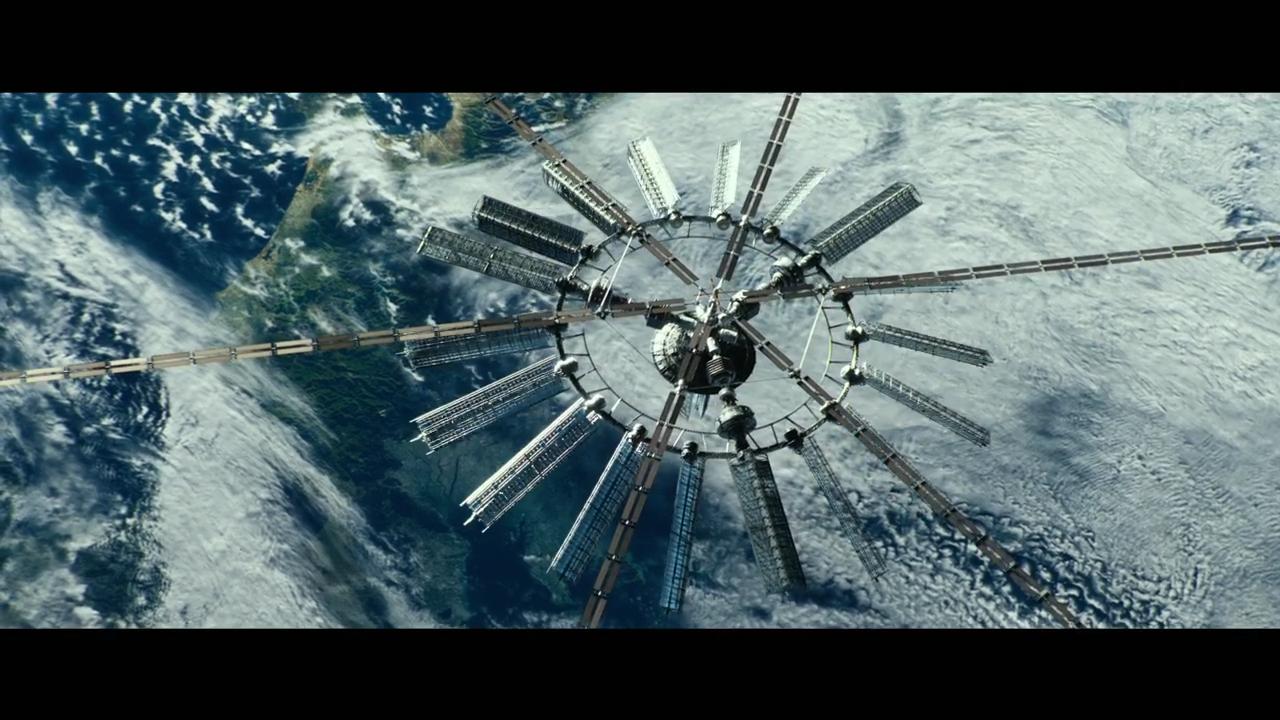

In Geostorm, there is an evil mastermind at work in the American government who has a plan to destroy the world with “extreme weather” via the wonderfully silly plot device of a satellite-based weather control system. The guilty party, the protagonists believe, is the President, but of course it isn’t.

We know it isn’t because Ed Harris keeps wandering through scenes, and instantly gives himself away for three reasons: he is the Secretary of State, a government role perhaps second only to Vice President in obvious evilness; he’s the most famous actor in any of his scenes; and, of course, he is Ed Harris, an actor who, if he played Jesus, would make Judas look trustworthy.

We know it isn’t because Ed Harris keeps wandering through scenes, and instantly gives himself away for three reasons: he is the Secretary of State, a government role perhaps second only to Vice President in obvious evilness; he’s the most famous actor in any of his scenes; and, of course, he is Ed Harris, an actor who, if he played Jesus, would make Judas look trustworthy.

But we also know it’s not the President because these global blockbusters in the Emmerich vein have a fascination with the role of the President. Geostorm writer-director-producer Dean Devlin co-wrote Independence Day, a film which takes this fascination past the point of parody, but the idea of the President as a uniquely incorruptible figure is a given any time America is under threat.

Geostorm is a movie that continually hints at the presence of international politics: the satellite system, we are constantly reminded, was built as a joint project under the U.S.’s jurisdiction; it is, of course, about to be handed over to the UN, which is treated as a powerful force opposed to the U.S. in the way it only is in blockbuster movies; and the cast is commendably international.

Geostorm is a movie that continually hints at the presence of international politics: the satellite system, we are constantly reminded, was built as a joint project under the U.S.’s jurisdiction; it is, of course, about to be handed over to the UN, which is treated as a powerful force opposed to the U.S. in the way it only is in blockbuster movies; and the cast is commendably international.

But the figure of the American president still serves as a lynchpin, pinning it to a specifically American sense of the world. And it’s because of this that the foisting of the role of conspirator off onto Harris is so revealing of its goals.

The weather satellite, we are constantly reminded, works perfectly, only became dangerous because of a virus. In the same way, the parasitically evil staff member reinforces the idea that the role of the President, and the country he stands for, works perfectly. Harris’ motives, which he helpfully rants about as he’s being dragged away, are to “turn the clock back to 1945, when America was on top of the world,” an opportunity the President manfully refuses.

In the final moments, we are set up for Gerard Butler’s impossibly fit engineer to sacrifice himself in the most Armageddon-aping way imaginable (someone, for some reason, has to stay behind to input codes manually). But he ultimately survives, because his sacrifice is unnecessary. Bruce Willis could sacrifice himself in Armageddon because he was doing it to protect his daughter and her fiancé. It was really the fullest expression of the father, as defined by terrible movies: to “guard” his daughter until she marries (her husband then taking the place of the father). Willis’ sacrifice was more of a dissolution than an absence.

In the final moments, we are set up for Gerard Butler’s impossibly fit engineer to sacrifice himself in the most Armageddon-aping way imaginable (someone, for some reason, has to stay behind to input codes manually). But he ultimately survives, because his sacrifice is unnecessary. Bruce Willis could sacrifice himself in Armageddon because he was doing it to protect his daughter and her fiancé. It was really the fullest expression of the father, as defined by terrible movies: to “guard” his daughter until she marries (her husband then taking the place of the father). Willis’ sacrifice was more of a dissolution than an absence.

Butler’s sacrifice is unnecessary because, in the choice to pass on power to “the world,” that sacrifice has already been made. America gives the world the gift of independence, and in doing so dissolves itself: it will always be the one who freed the world to be free, and thus can make a gift of what was inevitable. Maybe Devlin can adapt Barthelme’s The Dead Father next.