Skimming through Martin Buber’s two-volume collection of essays on the origins of Hasidism, I think I have realized what to call this loose category of fake world narratives, including The Truman Show: they are gnostic movies.

The idea of Gnosticism has been somewhat warped in the last 40 years (The Da Vinci Code, for example, has the audacity to claim they were suppressed for having a more human vision of Christ, when anyone with the least familiarity would tell you they had a far more divine version of Christ), but the basic premise is very close to these movies: that there is an evil god who has trapped human souls in bodies, and that the material world is, in fact, a massive prison to keep us controlled. But the knowledge, or gnosis, of the falseness of the world can be discovered by some humans, who can overcome their materiality and transcend to a new, superior world.

Buber saw Gnosticism as the complete opposite of true religion. True religion was, for him, about relationships between humans before God. The gnostic hopes to free themselves from all duty to other humans and to God by means of their secret knowledge. The knowledge, if I may put words in Buber’s mouth (at least the Buber of the Hasidic writings), frees the gnostic from their subjectivity. Knowledge is subject-independent; transcending the physical world of particularity, the gnostic has no responsibility to anyone.

Buber has often been accused of romanticizing the early Hasidic movement —justifiably — and I would say that he exaggerates the horrible evil of Gnosticism (as we’ll see in discussing The Matrix). But when it comes to a movie like The Truman Show (1998), I think his way of thinking is illuminating. If any of these movies live in the fantasy of Gnosticism, it’s this one in particular.

Buber has often been accused of romanticizing the early Hasidic movement —justifiably — and I would say that he exaggerates the horrible evil of Gnosticism (as we’ll see in discussing The Matrix). But when it comes to a movie like The Truman Show (1998), I think his way of thinking is illuminating. If any of these movies live in the fantasy of Gnosticism, it’s this one in particular.

I say this specifically because of the idea that acquiring the gnosis of the world being fake frees the knower from social responsibility. Of the 5 central movies here — Dark City (covered previously here), The Truman Show, eXistenZ, The Thirteenth Floor, and The Matrix), only The Matrix really has any sense of responsibility to others post-realization. In some, like Dark City, the question of “saving” the other prisoners is mostly ignored; in The Truman Show, it is taken to its most fantastic degree, in that there are really no other prisoners to be rescued.

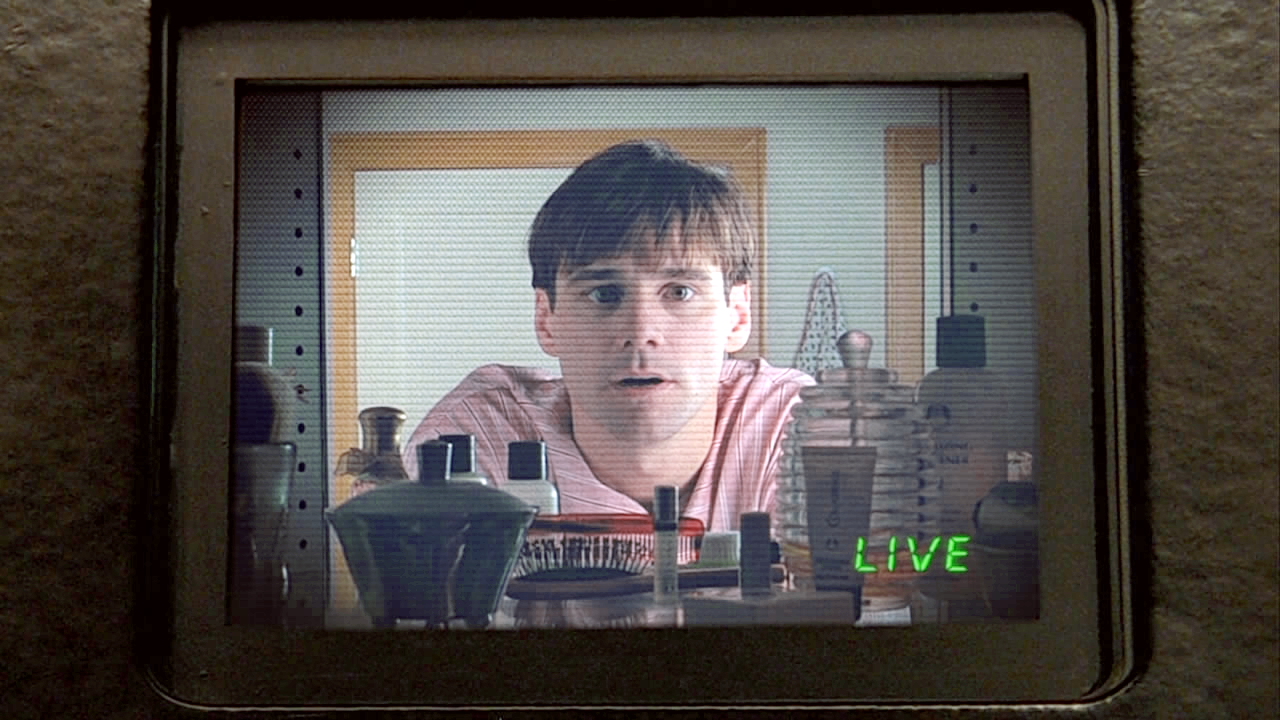

The first half of Truman is the apex of this fantasy, the fantasy of discovering some knowledge that frees you from being a subject. Realizing the world is fake, Jim Carrey is free to walk into traffic and run into random buildings. Mostly, though, his id-rampage seems to take as its object his wife. (Laura Linney’s performance is, frankly, remarkable, never making it clear how much of her fear is that the jig is up and how much is legitimate, but by the end, when he menaces her with a slicer, I found it genuinely upsetting.)

The first half of Truman is the apex of this fantasy, the fantasy of discovering some knowledge that frees you from being a subject. Realizing the world is fake, Jim Carrey is free to walk into traffic and run into random buildings. Mostly, though, his id-rampage seems to take as its object his wife. (Laura Linney’s performance is, frankly, remarkable, never making it clear how much of her fear is that the jig is up and how much is legitimate, but by the end, when he menaces her with a slicer, I found it genuinely upsetting.)

Carrey’s fantasy rampage, though, comes to an end before he actually manages to escape his prison. Why? In a striking maneuver (one which is yet another strike against the supposedly universal three-act structure), Truman turns on its heels halfway through; despite having clearly seen how fake his world is, he for some reason returns to normal, a move that makes such little character sense that it clearly signals a shift in narrative logic.

If Buber is right and Gnosticism is about dissolving social ties, then the first half is the properly gnostic half. But a complete dissolution of social ties, the fantasy of invisibility, isn’t emotionally satisfying for very long. The second half of Truman reorganizes the fantasy: the social ties are all restored, but they are all one-directional. They all head towards Carrey, and none head away.

If Buber is right and Gnosticism is about dissolving social ties, then the first half is the properly gnostic half. But a complete dissolution of social ties, the fantasy of invisibility, isn’t emotionally satisfying for very long. The second half of Truman reorganizes the fantasy: the social ties are all restored, but they are all one-directional. They all head towards Carrey, and none head away.

Carrey thus slips around the edges of the second half of the film. We spend roughly half an hour with Ed Harris’ director and with his fans in the real world. Even when he finally begins to make his proper escape, we spend our time with his hunters. He has no real presence.

I admit, this is a cursory look at the movie. (It probably shows that I frankly am not a fan.) What is interesting about it in the context of this set is the way it reveals that there is, in the modern version, a second half to the gnostic fantasy. It is not enough to merely be freed from the material world; the material world must be re-organized around the subject. We’ll get into the question of how that actually works with The Thirteenth Floor.