There’s a particular type of movie, the kind that depicts bourgeois capitalist decadence and excess, usually in the art world, or more specifically in the film world. La Dolce Vita is the iconic example, and all of the followers reference it; the recent examples I have in mind are The Great Beauty and Knight of Cups. They often depict listless men wandering from place to place through a city of decadence, sleeping with women and watching modern art performances.

In The Great Beauty, the scene that sticks in my mind is that of a child painting abstract expressionist paintings, while a crowd of adults stands around and praises her. Our protagonist, Jep, watches all of this, silently judging everyone for their shallowness: all these frauds, he thinks, enjoying the performance. They all speak of the child with hushed tones and abstract academic terms, tones and terms of which Jep is wholly suspicious and disdainful.

And yet, the paintings are beautiful, and the performance is beautiful, despite, or because, of the child that is their origin. This is how the film can eat its cake and critique it, too. We can be struck by the visual beauty of the paintings and the performance (and can forget the fact that, in the real art world, this form of Pollockian abstract expressionism died in 1964) and still assuage whatever guilt is left around (whether it is because the style is not politically relevant, or about not “getting” it, or about whether or not the fact that a child can make it undermines it as a form).

We get a similar moment in Knight of Cups, as the camera wanders away from Christian Bale’s meandering to watch an experimental film playing on a nightclub wall. The camera lingers for far longer than you would expect in these films, until one forgets the context and is simply watching an experimental film. It is actually by placing the works clearly within a narrative context that the viewer can ultimately engage with them outside of a clear context; if they were presented without context, simply as a film presented on its own in a theater, many viewers – myself included, sometimes – would be too distracted trying to contextualize it (what is the artist trying to say, is this all pretentious bullshit, will I seem pretentious if I enjoy it) to enjoy it without context.

This same ambivalence towards artistic decadence shows up in other places, too. I think primarily of The Neon Demon, a movie people insisted was supposed to be critical of misogyny. Despite what my friends told me, I didn’t see much criticism actually present – reading Refn’s interviews ahead of time, in which he argued that since most fashion magazines were run by women, the sexism was mostly women’s fault, probably dampened the possibility of seeing any. But me searching for that form of criticism distracted me from what I think I actually did enjoy about the movie itself. There is a visual brilliance happening, images of intensity that are ultimately not reducible to the question of whether or not the film is critical or uncritical of the underlying sexism. The intensities of the images of modeling overcome their apparent social causes.

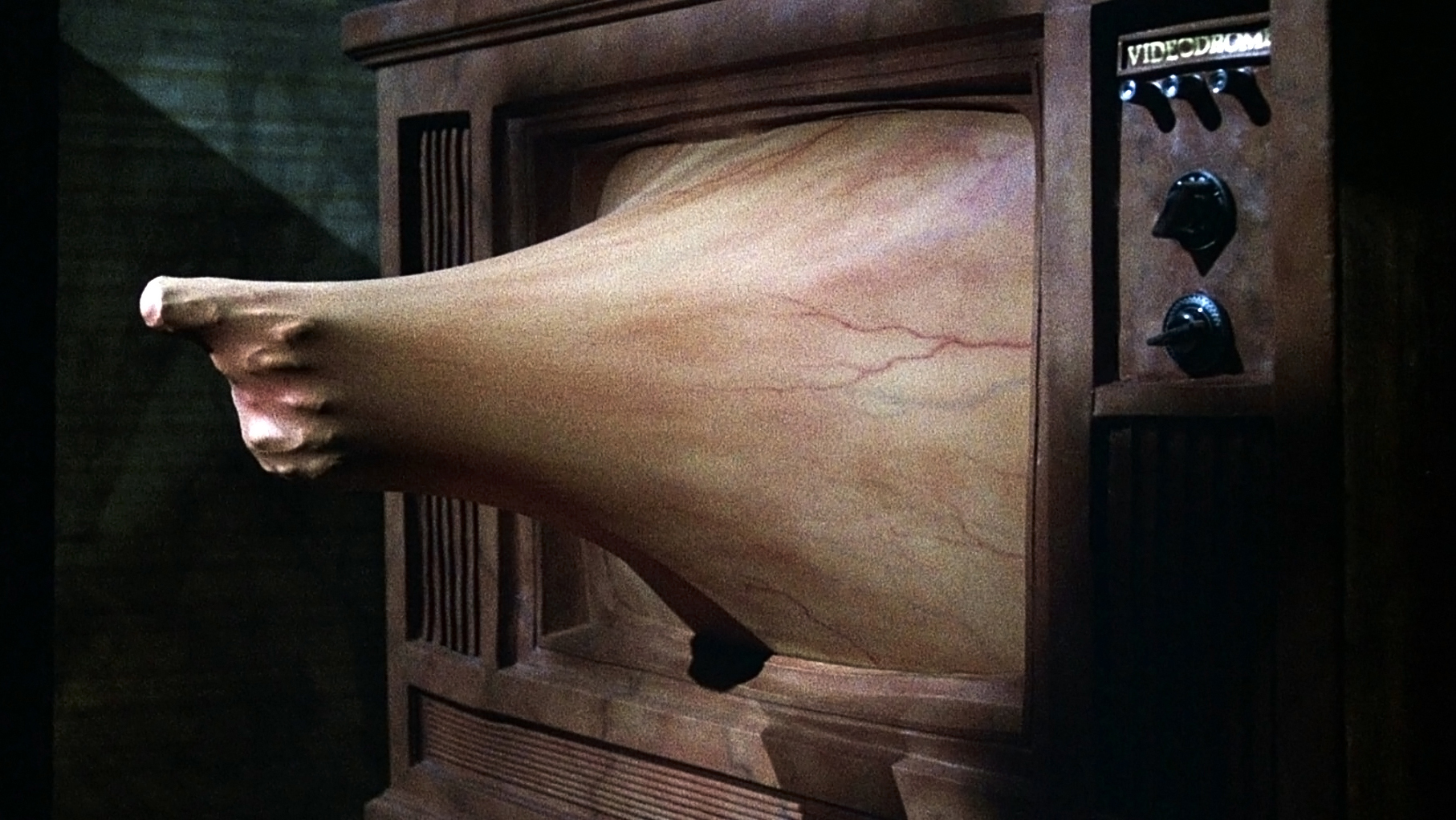

It also reminds me of a common criticism of Cronenberg: that he is ultimately a conservative figure, fearful of technology (at least before his turn from excessive to “realistic” at Spider). But ultimately, this is just an assumption: his creatures are excessive in a bizarre way, and we have been trained to assume this form of excess, of images that operate on the level of intensity rather than reasoning, is in some way satirical or critical. But in a pure sense, trying to read a film like Videodrome as a moralistic tale on any side, whether it is criticizing the new technology or those who are fearful of it, can’t explain the desire to watch and rewatch the movie. Like Gulliver’s Travels, if we think of the attempt to satirize as cause and the excessive images as effect, we miss the degree to which the images exceed their cause.

—

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that two of the most visually brilliant TV series of the last few years both revolve around mentally ill characters: Legion and Mr. Robot. Not just visually brilliant in a dull “One. Perfect. Shot” way, but brilliant at the level of the editing and timing of the visuals.

Both shows interrupt our understanding of cause and effect, making us always unclear what the base level of reality we are operating at is. Of course, that might sound boring as hell, like it will lead to another Inception-inspired conversation with insufferable film nerds: “Like, what is real, man? Is it just our perception of things?” Luckily, neither series does too much of that, but even when they do, it’s not ultimately relevant. Like the paintings, the brilliance that the concept of the characters’ mental dissociation inspires is not reducible to their contextual inspiration.

What it reminds me of, primarily, is one of those famous books that everyone references and few have read: Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus (PDF), volume one of Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (It is also one of those rare books, like How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read (PDF), which gives you permission to talk about it without having read it cover to cover.) The book is most infamous for its conception of schizophrenia as a positive way of life, one that creates images without being bogged down in concepts like cause or origin, and which psychology tries to destroy by “healing” it with rationality.

Now, obviously, if you have ever met a schizophrenic, this will seem absurd, even repugnant. It definitely can be read as an example of that extremely shallow valorization of mental illness that ignores the very real damage it causes to those afflicted and their family. I think this is actually where the co-authors diverge (despite their claims that as writers they are indissoluble, and that the writer “Deleuze & Guattari” cannot be reduced to either “Deleuze” or “Guattari”, or even “Deleuze” and “Guattari”).

Felix Guattari, radical psychoanalyst, is definitely searching for a Wilhelm Reich-ian openness to life that can help the mentally ill accept themselves, which may or may not be a helpful approach. Gilles Deleuze, on the contrary, is not particularly interested in the mentally ill as people, but as an idea, a way of thinking that is more than the actual, often miserable, lives of the mentally ill. It’s Deleuze, then who writes one of the most revealing lines in the book: “No, we have never met a schizophrenic.”

If D&G’s work is to have any impact on thinking about art, and, particularly, film – and it seems he/they are the new growing go-to French author, replacing Lacan – it is essential to understand that in the end, one should not assume that any author, but particularly Deleuze, is actually talking about what it looks like he/they are talking about. For example, it seems (from brief skimming through a few new books) that the new wave of Deleuze was delayed because film writers assumed that the most relevant books would be his two volumes on film, helpfully titled Cinema 1 and 2, when in fact those two books are very little help at all.

What I am trying to get at is this: these series, ostensibly about mental illness, are actually about something much broader: life today, in this culture, at this point in time. We should not be beholden to only using these modes of presentation, of seeing and editing, within the context of mental illness, because even though a desire to depict mental illness was the cause of their creation, it is not the totality of their effect.

—

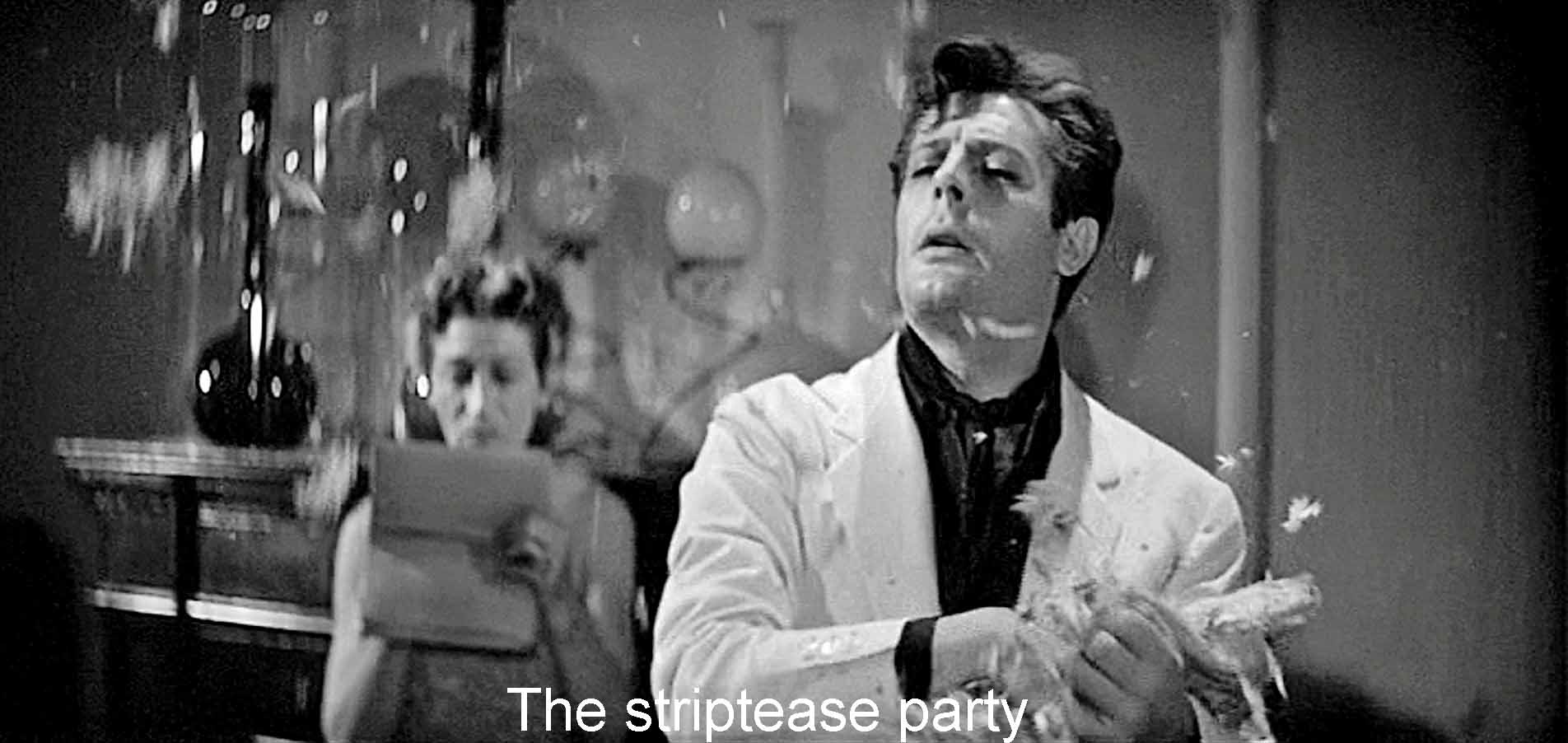

One image from La Dolce Vita always sticks in my mind. It is from one of the final doomed parties of the movie. Someone rips open a pillow and throws it in the air, and the feathers float in front of a window. I don’t care what the goals of the movie are, to depict a form of cultural burn-out – that image will always be serenely beautiful to me.

To make the connection explicit: this form of artistic decadence, endless parties of bodies swirling in free expression, is still of immense worth, regardless of the attempts a film makes to be satirical or critical. These parties are presented as the ultimate pleasures of the bourgeoisie, but the bourgeoisie in this context are taking their fullest place as a class: by accruing material wealth and freeing themselves from physical desire, they can fully express themselves.

Their crime is not expressing themselves fully, but privating that right to expression from others. This is how we can all participate in their excess with just the cost of a movie ticket. (This would require a longer, fuller essay by someone more qualified than me, but I think this point counteracts the constant criticism of the “materialism” of young black men and popular rap music.)

In this excess of effect over and against cause is united Legion and Mr. Robot’s depictions of mental illness; La Dolce Vita, Knight of Cups, and The Great Beauty’s depictions of the film world’s gluttony; Cronenberg’s ambiguous criticisms of “the new flesh”; even Scorsese’s two-faced critiques of excessive masculinity, whether in mobster or capitalist form.

It is absolutely possible to go too far in this celebration of excess. Causes are still real. Sexism is still real. Racism is still real. It is too easy to end up reading all absurd excess as a positive, joyful object – a mistake Deleuze and Guattari make in their somewhat absurd reading of Kafka. I don’t know how to synthesize these two points together, but it is definitely one of the key projects of future analysis of art, not simply more ideological criticism or lazy populism.