Until his sad, untimely death last month, Bill Paxton was one of the true under-celebrated actors of his generation. As a genre star, he had legions of dedicated fans (and apparently an army of co-stars eager to sing his praises as a decent, hard-working, charming guy to boot), but he always seemed more likely to register with casual movie-goers as That Guy. His few directing credits, including Frailty, garnered even less mainstream notice, though no small amount of cult adoration.

Frailty is as bare-bones and elemental as horror comes, but Paxton builds real terror from the mundane. The story of a working-class dad (Paxton) convinced he can see devils masquerading as regular people, and so is tasked with ridding the world of them, it’s devoid of special effects or even jump-scares. The horror lies in his maniac commitment to the mission — his voice almost never wavers, nor is he the kind of guy who needs to shout — and the ways he enlists his sons help to get the job done.

Matthew McConaughey plays one of those children, now grown and telling the story to a skeptical detective (the always-welcome Powers Boothe) who’s tracking a serial killer. Alongside John Sayles’ essential Lone Star, it might be his best performance, pre-McConaissance: all stoner Texan drawl and a fierce commitment he seems to have picked up from his dad, McConaughey helps set the uneasy mood.

There’s nothing groundbreaking in Paxton’s direction of Frailty: “workmanlike” is probably the word, with a particular affection for fades between past and present. But that same, almost documentary feel imbues the narrative with a cold chill, as the detective discovers some really unsettling corners of a single man’s faith and its effects on his family.

“Frailty” is a strange title for the film: does it refer to the weakness of the flesh? The ease with which children can be imprinted? The thin line that divides faith and madness? When Paxton brings up the story of Isaac, it comes as no surprise. Frailty places us in a Kierkegaardian grey area, where visions from God could just as easily be indications of mental illness, but they can’t, morally, be shrugged off.

Paxton will be lovingly remembered by anyone who grew up watching Alien, The Terminator, or Predator 2 (the superior Predator; come at me) … not to mention Near Dark, Titanic, Apollo 13, Twister, True Lies, or HBO’s Big Love.

But in Frailty, we see something of a more personal vision emerge, focused on conflict between the rational view of life as it’s lived and the absurd intimations of the divine. As usual with such things, when done well, Frailty is genuinely terrifying.

Quick Links

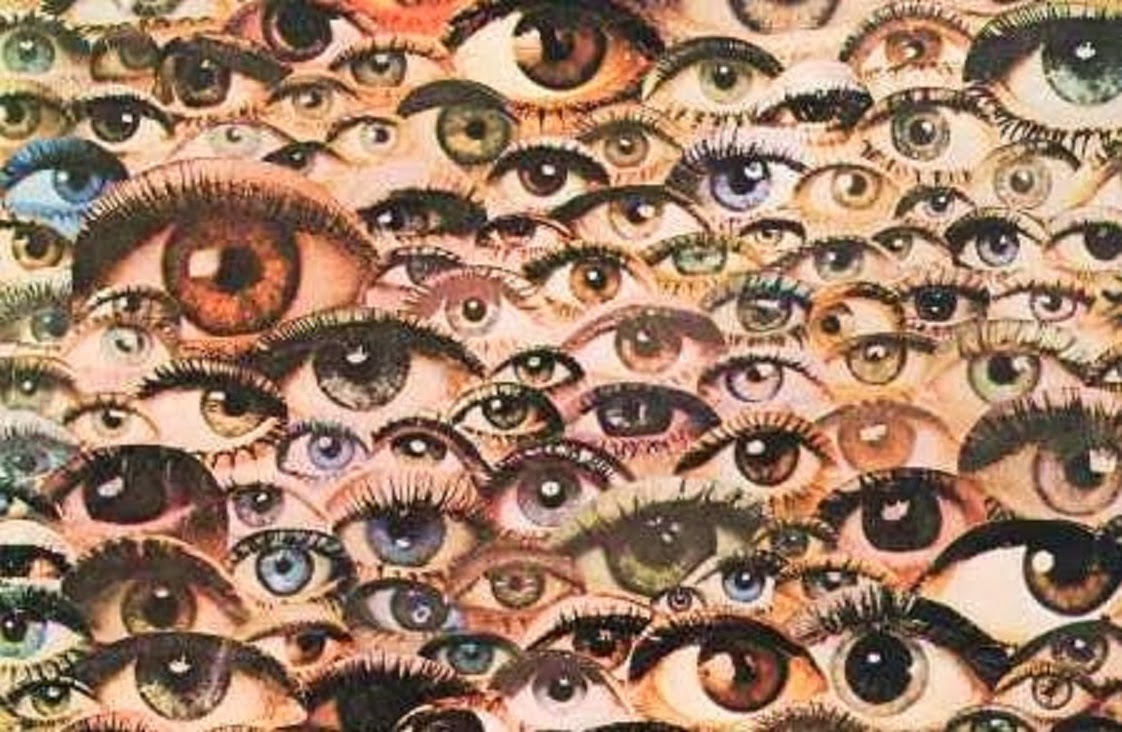

Frank and Caroline Mouris’ experimental short somehow garnered an Oscar in 1974, despite being weird as hell. The 70s! It was a different time.

Composed entirely of magazine clippings and other found art, Frank Film overlays dual audio tracks that vie for the viewer’s attention. The result is sometimes a maddening cacophony and sometimes a kind of harmony or counterpoint, as the detritus of modern images flash before us and a narrator tells the story of how he came to make the film. It’s insane, postmodern, expertly accomplished, and somehow counter-intuitively watchable, or at least absorbing.

I would never specifically advocate mind-altering drugs as a prerequisite for viewing a film, but in this case, it probably can’t hurt.

(Streaming on LeCinemaClub through 3/5)

You know what else was a different time? The 90s. And nothing says “the 90s” quite as much as a coven of feminist witches featuring Fairuza Balk and Neve Campbell.

(Streaming on Netflix)

Have you watched the first and greatest of the Christopher Guest mockumentaries recently? Why not? It’s hilarious.

Not long ago, the good folks at The Next Picture Show talked about Spinal Tap‘s influence on The Lonely Island and the hilarious Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping, and one aspect of the discussion that jumps out is the miracle of editing and compression in Guest’s masterpiece. There is hardly a wasted scene here: the film is impossibly tight for an unscripted goof, distinguishing it from some of its imitators (including Guest’s later work).

“It goes to 11.” “Perhaps we could rearrange the choreography, so as not to trod upon it.” “A fine line between clever and stupid.” “Never found out whose vomit it was.”

We could go on all day. Instead, let’s just rewatch This Is Spinal Tap.

(Streaming on Netflix)

Sticking with the fake documentary, Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement’s What We Do In The Shadows carries on the tradition in admirable fashion. Equal parts sweet and ridiculous, their film reimagines the single-camera aesthetic, giving us something like The Real World except about vampires. Both leads (and directors, and writers) are hilarious — fans of Flight of the Conchords and Hunt for the Wilderpeople will be unsurprised.

The basic premise of ageless vampires sharing a group house in Wellington, New Zealand is funny enough, but What We Do In The Shadows is also filled with stellar improv and some knowing nods to the horror genre in general. (I’m particularly fond of the brief appearance of Rhys Darby — Murray, from the Conchords — as a rather proper lycanthrope leader, with no tolerance for offensive language: “Hey, now. We’re werewolves, not swear-wolves.”)

(Streaming on Amazon Prime)