Unlike my pal Rick Kelley—who once told me, on the record, that “jazz sucks”—I actually like jazz music quite a bit, but I’m not great at just listening to it with full concentration. When my mind wanders, I sometimes play a game: “How would a rock music critic write about this?” You know the kind of awful prose I’m talking about, the kind written by people completely out of their depth and end up falling into the same clichés, something like:

Ahmed Jamal never plays a note he doesn’t want to. He hangs back until the right moment, then strikes like a cobra—a sudden arpeggio leaping upwards towards the light, a sudden tumble down the stairs that turns into an elegiac lament for a lost pet…

The old Pitchfork was the king of this, culminating in one of the most embarrassing, awful reviews ever written, their review of John Coltrane’s Live at the Village Vanguard: The Master Takes, which was written entirely in a funetik approximation of what a white dude thinks a “jazz cat” talks like. (No one brings this kind of bullshit out of writers like Coltrane or Charlie Parker, and we’ll get to the latter in a minute.) Only Billy Crystal’s approximation of the same, mostly imaginary stereotype comes close to being as embarrassing.

Maybe the only person to do this style actually well is Thomas Pynchon in Gravity’s Rainbow, where in a hazy dream either one of our protagonists or an omniscient narrator or some mixture of the two recounts the audience’s reaction to hearing Parker play. Beyond just the complicated interplay of Pynchon’s self-awareness of whiteness and his protagonists’ complete lack of it (at least in GR), it works in that context because we are experiencing the first wave of discovery of Parker’s early bop style. That breathless grasping is an old language trying to keep up with new discovery.

But if 80 years later, all jazz represents to people is this abstract “newness,” a freedom that doesn’t have any real content, what good is it? It is no coincidence that this kind of empty fetishism of the abstractness of jazz focuses on, essentially, the 50s and 60s, a period in which jazz went through the same modern development that so many art forms did, in which the playing field is cleared of anything unnecessary so the game can be played in earnest. How many of these critics talk endlessly about The Shape of Jazz to Come, but have never heard Coleman’s later masterpieces, like Sound Grammar or Science Fiction, which fulfill the promise of which Jazz to Come was only the shape? Did they miss the essentially forward-looking nature of the album’s title?

This is why, despite the book falling into the other standard traps of the Specialist Music Critic Writes a Book genre, Ted Gioia’s recent How to Listen to Jazz never falls prey to this kind of breathless nonsense. Gioia actually can play jazz, so he knows the language. He doesn’t use the language—he doesn’t tell the reader about why it was important when pianists started adding left-handed voicings to Bud Powell voicings, or anything technical like that—but it is always obvious in his descriptions of musicians that he actually knows the technical side.

But that kind of writing and thinking about jazz is nothing new.

—

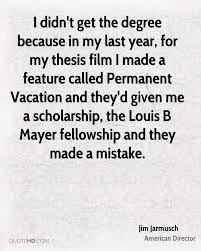

If you know that Permanent Vacation is Jim Jarmusch’s first film, made right as he was leaving film school, you probably can imagine much of its style. If you know that it comes as a bonus feature on the Criterion DVD of Stranger than Paradise, you can probably imagine it completely. There is a particular style to those early, supplementary films of directors of this era, like Linklater’s It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books (which comes on the DVD set of Slacker) or any of the Wenders movies collected in The Road Trilogy box set.

The protagonist will be a shiftless young man, of roughly the director’s age. He may be in a relationship, but will be drifting away from his partner, who does not understand his listlessness. The middle part of the film—which is refreshingly short in Vacation, but can stretch up to two hours in Wenders’ hands—will consist of the protagonist wandering from vignette to vignette, doing very little. He will be told at least one story by a boisterous, probably homeless person. He will go to see a movie, usually one of those top-tier genre films—the type that the Cahiers folk would like. (In Vacation it’s Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents.) There will at least one person of color, who will be larger than life and mentally unwell. (Vacation gives us a Latina woman, screaming cat-like in an alley.) The protagonist will often end by leaving for a new town, in which he can wander aimlessly. And, of course, the protagonist will usually love jazz.

In the American version of this movie, at least, it’s usually jazz—Wenders replaces it with American rock music. (His complete disregard for American copyright is why some of his early movies, like The Goalkeeper’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, are hard to get in Region 1—the recent remaster of Wenders’ films was forced to replace most of the music.) Vacation’s protagonist, Allie Parker, tells us in the opening narration if he has a kid he’ll name him Charlie—“like Charlie Parker”, he explains for the benefit of the slower audience members. Just after telling us this and preening in a mirror, he dances to a jazz record.

The requisite story the protagonist listens to, mentioned above, is about a jazz musician who gets depressed because Americans don’t like the newness of his sound, so he moves to Europe—and finds they don’t like it, either. Shortly thereafter, Allie runs into a saxophonist on the street, played by his soon-to-be-long-time collaborator, John Lurie, who asks him, “What do you want to hear, kid?’ “I don’t care,” he responds, “as long as it’s vibrating, bugged-out sound. Man, what a sound,” he responds, in a monotone that almost sounds sarcastic. Lurie lets out a few notes, and the kid walks away, satisfied.

I don’t think that it’s a coincidence that Wenders use of American popular music as a whole and Jarmusch’s use of jazz here are analogous. The point is that in both instances, the music represents an energy that’s somewhere else. That passionate jouissance is always both present and absent: it’s on a record, or in a jukebox, or in a story, but never completely present. (This may be why Allie immediately becomes bored when Lurie starts playing the saxophone.)

There’s a definite element of coding, too. The energy contained in jazz music is related to the inevitable “larger than life” people of color, who often burst with an energy the other characters lack. (The man who tells Allie the story of the jazz musician, who can barely get through a sentence without bursting into laughter, is black, for instance. In fact, it’s worth noting that the only people who laugh in the movie are the two black characters and a white woman in an insane asylum.)

—

I suppose what I’m getting at is this: Jazz is not good at representing anything. There have been some arguments about jazz in movies lately, with Whiplash and La La Land being particular battlegrounds. (Note: I haven’t seen the latter, and only really know there are arguments about it from Rick.)

People have always wanted to overload jazz with semantic meaning. The American government’s use of it is a particularly fascinating case. During the Cold War, American jazz musicians were sent on tours, as the musical form was seen to represent the freedom of the American way. This is specifically the context of Adorno’s much, and unfairly, maligned article on jazz (PDF), which pointed out that while it may seem that each musician has freedom—they can stand up and perform their solo—at the end, they must be reabsorbed into the group.

One would think that, as a musician himself, Adorno wouldn’t fall for this obsessive overloading of music’s semantics, but that wasn’t a skill he had. (He considered Schoenberg just about the greatest composer around, but, when Schoenberg heard his reasons, he is said to have wondered “if [Adorno] has heard one note I composed.”)

This is not to say music is not political—the new musicology, partially inspired by Adorno, has produced any number of brilliant critiques. Even jazz itself has had deep political meanings—but always from within, like Max Roach’s We Insist! or Ornette Coleman’s This Is Our Music (which also serves as the title of a wonderful book on the relationship between African nationalism and free jazz).

Jazz on its own doesn’t represent anything very well. It’s a field as wide as rock music, or pop music, and filled with as much diversity. And when artists and critics and philosophers fetishize it as meaningful as a whole, they tend to do so by limiting the actual artistry behind it. Jazz is often reduced to a pure expression of the artist’s interior, and their technical skill and intelligence is often ignored. (One of those critical crimes that Gioia commits is related: the tendency to sand down the rough edges of musicians by pointing out the beauty of the music. Gioia says he can’t fully believe the stories about Miles Davis being an abusive, awful person, because he “makes such beautiful music”.)

diversity. And when artists and critics and philosophers fetishize it as meaningful as a whole, they tend to do so by limiting the actual artistry behind it. Jazz is often reduced to a pure expression of the artist’s interior, and their technical skill and intelligence is often ignored. (One of those critical crimes that Gioia commits is related: the tendency to sand down the rough edges of musicians by pointing out the beauty of the music. Gioia says he can’t fully believe the stories about Miles Davis being an abusive, awful person, because he “makes such beautiful music”.)

What I am trying to get at is the laziness of the gatekeepers complaining Whiplash or La La Land or anything else isn’t “really” about jazz, or isn’t about “real” jazz. The importance isn’t the music itself—it’s what it means to the characters that’s important, because that’s all there is. What these people who complain about people not “getting it” actually want is something more like Permanent Vacation, which is more entrenched in a freer period of jazz music—but the music holds up that meaning just as little.

Besides, as Rick said: a lot of jazz does, actually, suck.

This is a guest post from Liz Lerner. It was originally posted on her site Destroy All Critics.