It’s relatively rare for a film to begin with a mission statement, but Man With A Movie Camera — Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Constructivist ode to man, machine, and revolution — is not an ordinary film.

Before Vertov presents a dizzying, self-reflexive montage of a day in the life of post-Revolutionary Russia, he informs the viewer:

THIS FILM PRESENTS AN EXPERIMENT IN THE CINEMATIC COMMUNICATION OF VISIBLE EVENTS

WITHOUT THE AID OF INTERTITLES

WITHOUT THE AID OF A SCENARIO

WITHOUT THE AID OF THEATER

THE EXPERIMENTAL WORK AIMS AT CREATING A TRULY INTERNATIONAL ABSOLUTE LANGUAGE OF CINEMA BASED ON ITS TOTAL SEPARATION FROM THE LANGUAGE OF THEATER AND LITERATURE.

It’s hard to imagine a more succinct statement of principle (though that’s not enough to stop one YouTube commenter from complaining, “Honestly, I don’t get the point of this film. Yes, you can look at its history of advancing editing, but right now, it’s just a bunch of images to me. There’s no storytelling going on.” Oh well.)

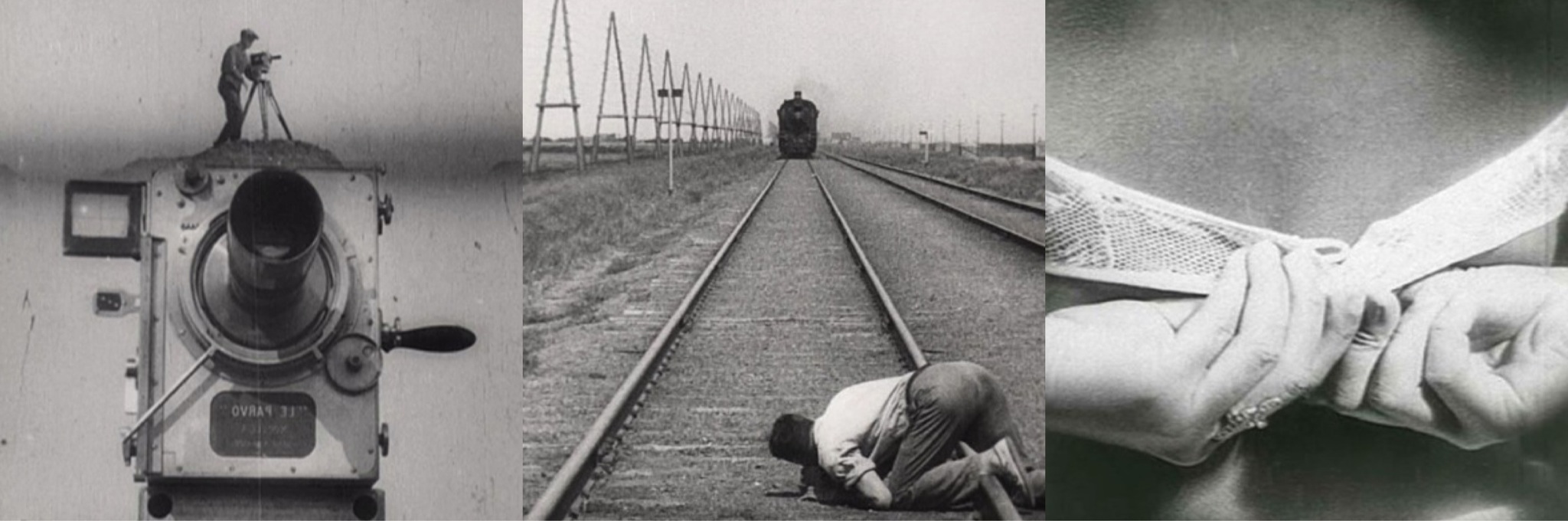

Vertov is true to his word. Drawing on Eisenstein’s theory and practice of montage and advancing some of the techniques he himself developed in the earlier Enthusiasm, Man With A Movie Camera dispenses entirely with story and character, attempting to elicit ideas and emotion from image and contrast alone. So we witness work, leisure, a couple getting divorced, a baby being born, a woman washing her face and getting dressed, sport, trains arriving and departing, the industrial swirl of a modern city. Vertov’s wife and creative partner Elisaveta Svilova edits Man With A Movie Camera at a fever pitch, with an average shot length of “2.3 seconds, which is four times faster than most films of that time and the speed of the average action film made today.”

As Noel Murray writes, the two “cut together images sometimes due to their thematic connections, but just as often because they liked the emotional effect of the juxtapositions.” The splashes of water to the woman’s face as she starts her day cut immediately to power washers cleaning off shop storefronts at dawn, perhaps implying the unity of the individual and social processes.

Images of bourgeois grooming in hair salons collide with washer-women, hands immersed in soapy water. The trains that serve as a recurring motif are intercut with divers and swimmers and shop-floor workers. Bureaucratic terminations of marriages fold into delivery room footage of a baby being born. There is no pedantic reading to be had, aided by the guiding hand of a storyteller; we’re immersed in each image, and in the relations that seem to arise between them. Man With A Movie Camera is intoxicated by the images themselves, the resonances between them, and the lives they depict.

At the same time, Vertov undercuts this notion of directorial absence with frequent self-referentiality, from the title on down. The man with a movie camera is the closest thing we have to an on-screen protagonist. He is everywhere: through superimposition, he is on top of buildings and vanishes into a glass of beer at a pub; he’s riding alongside the action in a speeding car; he’s climbing a railroad trellis, and later positioning himself on the track itself to get a shot of a train’s undercarriage.

In fact, he’s the first person we meet, threading his film into a projector, as an audience takes their seats to watch the film of their lives. There is an emphasis on capturing these images, the work that it entails, and the connection between the machinery of city life and the machinery of representation.

Vertov’s revolutionary affiliation consumes the film he has made about it — we even see Svilova snipping away at the film, as the frame rate slows to a series of stills. At the end of Man With A Movie Camera, double exposure allows the captured city to fold in on itself, as demonstrative a portrait of creative destruction as the medium allowed.

Watching the film today, the paradox is striking. In Man With A Movie Camera, we have a directorless cinema “the true purpose [of which] was just to capture scenes of daily life, as naturally as possible,” but also one in which the politics and presence of the director are inextricable from the sequence of images and their impact. This conflict would animate documentary experiments like Jean Vigo’s À propos de Nice (released the following year) to Riefenstahl, not to mention present day debates over the very possibility of apoliticism of the image. Particularly in the current political climate, these are not debates that are going away.

\

The far-reaching influence of Man With A Movie Camera is hard to overstate. Ben Nicholson emphasizes Vertov’s (literally) revolutionary use of five specific techniques — the dissolve, slow motion, stop motion, split screen, and double exposure — and examples of their later deployment in everything from Doctor Zhivago to Charlie’s Angels, Carrie to The Matrix, Star Wars to Inception. None of the techniques originated with Man With A Movie Camera, but their combined weight in Vertov’s experiment made a lasting impression.

The film itself is an aesthetic wonder. As an interrogation of the politics of representation, it continues to raise more questions than it answers.

By filming in three cities and not naming any of them, Vertov had a wider focus: His film was about The City, and The Cinema, and The Man With a Movie Camera. It was about the act of seeing, being seen, preparing to see, processing what had been seen, and finally seeing it. It made explicit and poetic the astonishing gift the cinema made possible, of arranging what we see, ordering it, imposing a rhythm and language on it, and transcending it. Godard once said “The cinema is life at 24 frames per second.” Wrong. That’s what life is. The Cinema only starts with the 24 frames — and besides, in the silent era it was closer to 18 fps. It’s what you do after you have your frames that makes it Cinema.