I’ve already covered my favorite films that came out in 2015. But that is only half the story. First-watches are at least as important, and probably more so.

Here are some of the films that meant the most to me that I saw this year, regardless of when they came out.

There are probably a number of unifying threads between them — for one thing, it seems, in retrospect, I was struck most by simple stories told well.

Maybe I’m getting older, and there’s a certain appeal to that kind of storytelling — things that strip away the unnecessary veneer to get at more basic truths. On the other hand, children love simple stories, too. Maybe that’s a distinction without a difference.

I originally had a much longer list, but I am very lazy, and writing things is very hard. So — leaving out such minor titles as Tokyo Story, Wild Strawberries, and the work of Chris Marker — here are 10 films (ok, 12) that I loved in 2015.

If you find yourself at a loss for a thing to watch, may I suggest the following for your 2016. In chronological order:

- Trouble In Paradise – Ernst Lubistch (1932)

A charming, hilarious, bawdy pre-Code love triangle filled with shenanigans and good-natured intrigue, as unrepentant thieves become glamorous protagonists. The “Lubitsch touch”, whatever that means, is everywhere. And the dialogue is scandalously delightful:

“If I were your father, which fortunately I am not, and you made any attempt to handle your own business affairs, I would give you a good spanking — in a business way, of course.”

“What would you do if you were my secretary?”

“The same thing.”

“You’re hired.”

I’m not sure you could get away with that now, 84 years later.

- The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943); A Matter of Life and Death (1946); The Red Shoes (1948) – Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

2015 was, among other things, the year of The Archers for me.

We all have blind spots, but this was a particularly acute one for me: despite Powell and Pressburger’s prominence in the history of British cinema, and despite their enormous influence on their greatest fan, Martin Scorcese, I hadn’t seen a single one of their films. Suffice to say, I was missing out.

Shot through with playful romanticism, visual splendor, a willingness to combine forms at will, and consistently inventive narrative structures, the triumvirate of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, and The Red Shoes dominated my cinematic education this year. (I’ve yet to see Black Narcissus, but that will be remedied quickly … followed by all the rest.)

Colonel Blimp’s epic scope and nuanced characters, AMOLAD’s existential beauty and Technicolor fantasias, and the unparalleled, balletic intricacy of The Red Shoes’ adaptation of Hans Christian Anderson, with the performances of Deborah Kerr, Moira Shearer, David Niven … I finished each of these and simply shook my head in disbelief that it had taken me so long. And then promptly went and read Powell’s two-volume memoirs.

Of all the films on this list, these three stand out as examples of why you should never be embarrassed by the famous titles you haven’t seen. That just means you have so much to look forward to.

- The Best Years of Our Lives – William Wyler (1946)

Wyler’s ode to the struggles, triumphs, friendships, and melancholy in the U.S. following the Second World War elicits great, nuanced performances from all involved. With a yearning, realist tone pervading its story of veterans readjusting in ways big and small to civilian life, it’s an elegy for a time already passed and a hopeful nod to a new day – two meanings expertly, and sadly, encapsulated in its title. Its three interweaving stories form a tight narrative structure, and each are moving, and the ending feels totally earned. For once, closing on a wedding isn’t corny at all. Try not to cry; I dare you.

- Letter From An Unknown Woman – Max Ophüls (1948)

A ravishing melodrama told in a series of interweaving flashbacks, Ophüls’ film casts something of a spell. We know where we’re going, but, like the carnival tour of “foreign lands” on which lovers Jean Fontaine and Louis Jordan embark mid-way through the film, there’s no way out. Artifice, yearning, and responsibility are emphasized — those three never settle into a comfortable match. Not in 1948 and not now.

Letter From An Unknown Woman is often characterized as “a weepie,” that utterly sexist throw-off genre delineation that seems to assume pictures about women’s desires and experiences are always of fundamentally less interest than their male counterparts. That’s an idiotic notion to start with and one which barely needs a counter-argument, but if you’re looking for one, this is as good a place to start as any. On the other hand, the film isn’t interested in such arguments. It’s a narrative masterpiece and as deeply felt as anything I saw all year.

- Orpheus – Jean Cocteau (1950)

As part of the Counter-Programming The Great Movies series, I watched and reviewed Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet earlier in 2015, but that entry in his Trilogy pales in comparison to the inventiveness of Orpheus.

Small gestures – a hand putting on a glove, a step through a magic mirror, a walk down a hall – are invested with all the magic of myth. Cocteau, poet and visual dreamer, conjured something strange here, with the most basic of camera effects. In the age of CGI, it still works, and it’s a little startling. It might sound fussy or like Abe Simpson shouting at a cloud, but it’s true — the best magic tricks don’t need that much help from your new-fangled machines. The old machines can still amaze.

- Ikiru – Akira Kurosawa (1952)

I have seen many of Kurosawa’s films, and but it wasn’t until this year I discovered my favorite.

Ikiru is a simple story – A man who knows he will die realizes how little he’s actually managed to accomplish in all his days of work, and decides to do one last meaningful thing before his time is up. He will see that a park is built, and he will help the community of women who demanded it through the same bureaucracy that has crushed him.

That’s it.

Out of this, Kurosawa constructs a humanist tale affirming that, even in the face of oblivion, we can find meaning through human connection and acts of kindness. Whether anyone understands us or not.

The film says: Let them debate our legacy after we’re gone. In the meantime, make of your life what you can. Ikiru is the most hopeful movie I’ve ever seen, and it’s about a guy with stomach cancer. Only a master filmmaker could possibly make that true.

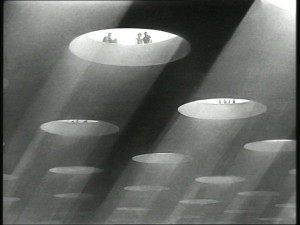

- Goke, Body Snatcher From Hell – Hajime Sato (1968)

Here’s a film that announces its intentions and aesthetic right in the title.

Does it sound awesome to you? Then you will probably enjoy it.

Need more convincing? How about this tagline: “A fiendish vampire from a strange world in outer space drains his victims’ blood and turns them into weird corpses!”

Macabre, animated by anxieties about nuclear apocalypse, and efficiently clocking in at barely over an hour, it delivers the sci-fi goods. If you are one of those people who considers such things good. I am one of those people.

- Head – Bob Rafelson (1968)

Bob Rafelson essentially co-founded the New Hollywood, directed the bona-fide classic Five Easy Pieces with Jack Nicholson in the lead, and generally helped provide the early backbone for counter-culture filmmaking in the late 60s and early 70s.But the weird genius at work in his debut Head has to be seen to be believed.

A Monkees vehicle that seems to find the Monkees bizarrely (and admirably) committed to torpedoing their own pre-fab careers, it’s a surreal slice of psychedelia, equal parts tripped-out be-in and stream-of-consciousness, anti-plot cinematic meandering.

With a walk-on part for Frank Zappa and a whole lot of gleeful loathing for themselves and the system that made them, it’s like the stars’ turned their enormously popular sit-com inside out. Watching it feels a bit like going insane – if your descent into madness regularly featured the Monkees bantering in an empty black room. I know mine probably will.

- Where Is The Friend’s Home – Abbas Kiarostami (1987)

As directed by Kiarostami, eight-year-old Ahmed seems in perpetual danger of being crushed by the world, the frame pressing him down. He’s a small boy on a simple quest – returning a schoolbook to a friend. This leads to a great and terrifying adventure, in which he travels from village to village, slowly expanding the scope of his world.

“The Friend” doubles as a name for the Prophet, adding a deep, spiritual nuance to the tale. The child, a naif, has to buck tradition, local customs, and the finger-wagging of shrill adults to do what he knows is right. Here is a fable that captures the confusion of childhood, but infuses it with the richness of adult doubt. It’s gripping and lovely.

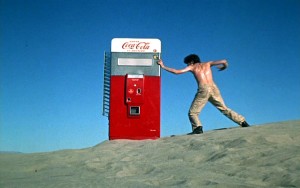

- The Straight Story – David Lynch (1999)

Apparently, in 2015, I was rather taken by stories of simple people doing simple things. David Lynch’s The Straight Story may be the pinnacle of this sensibility.

I love Lynch’s skewed visions, from Eraserhead through Mulholland Drive (sorry, I’ve yet to make it through Inland Empire), and knew going in that this film was famous for how dramatically it diverged from auteurist expectation. Well, it does and it doesn’t.

Richard Farnsworth learns his brother is dying. He can’t drive a car, but he has to go see him, patch things up (whatever those things are that need patching). So he gets on a tractor in Laurens, Iowa and heads out for Mt. Zion, Wisconsin. His tractor breaks down. He has to start again. He does. It’s the world’s slowest road-trip. Along the way, he meets some people. Weird things happen, in a G-rated sort of way. It’s just a man and his tractor, some gorgeous shots of the Midwest, and an old man who wants to say goodbye.

Like Kurosawa in Ikiru, Lynch spins something entirely magical out of this. The Straight Story makes clear something I should’ve known about Lynch a long time ago – his corn-fed, off-kilter awkwardness isn’t entirely an act. There is deep love for people and place here, and Farnsworth is utterly amazing, a quiet performance as a quiet man in a quiet film, quietly but resolutely pushing forward in a straight line to achieve a simple end. I loved every minute of it.