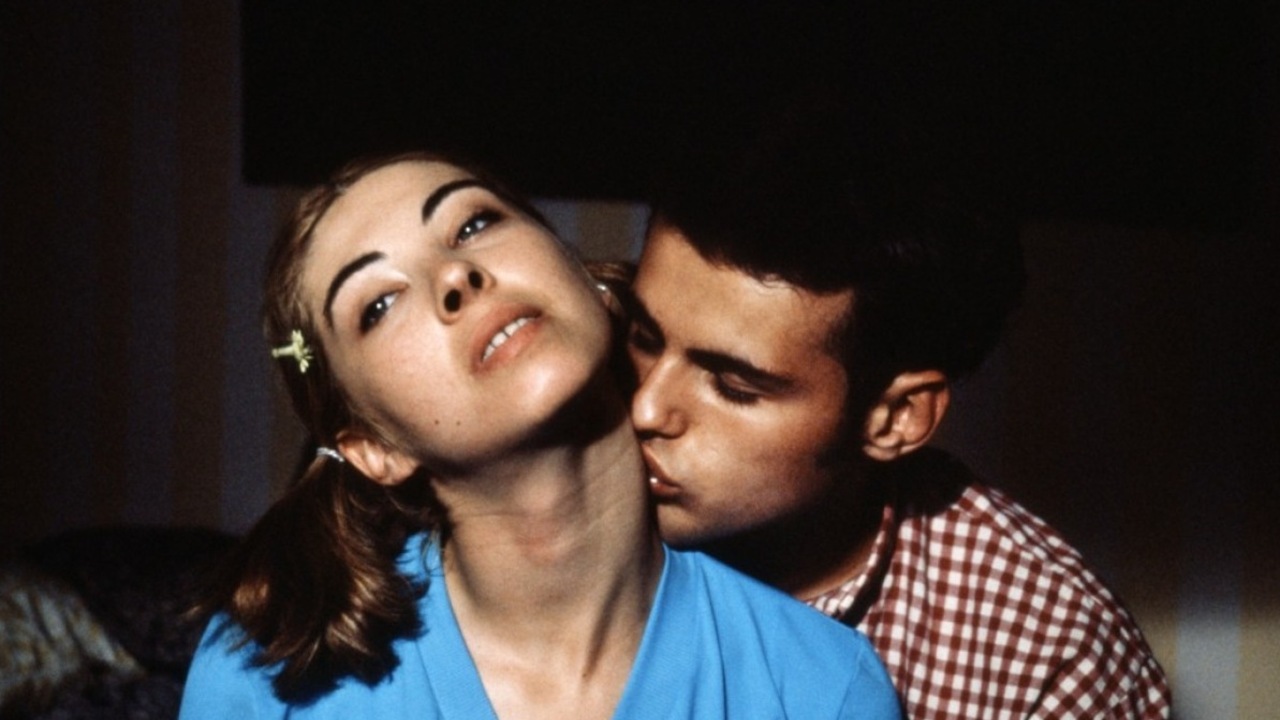

The Wild Boys, Bertrand Mandico’s feverish and gleefully overstuffed debut feature, is many things at once, and not all of those things make immediate sense together. It’s a highly theatrical coming-of-age story set on the high seas, featuring boys played by women becoming men who become women.

September 2018

With several months still to go, and no shortage of forthcoming releases, there’s already been talk about 2018 as The Year of Documentaries. Heather Lenz’s Kusama: Infinity probably won’t top too many year-end lists of these, but it merits inclusion: a solid, empathetic look at an artist whose body of work deserves the attention it’s finally receiving.

No one told me about Yılmaz Güney, and I find this extremely rude.

Sure, I could’ve discovered one of the most famous figures of Turkish cinema on my own. It probably wouldn’t have been too difficult to uncover “the most seismic and controversial cultural figure of his generation and a catalyst for a new era of politically engaged filmmaking,” in Bilge Ebiri’s description, a writer and director who “remains an icon in Turkey to this day, his face gracing posters in coffeehouses and theaters, his name regularly invoked by contemporary filmmakers.”

I will say, “Mandy feels like the last movie I will ever be disappointed by.” And you will say, “That’s ridiculous. We will all go on getting our hopes up and sometimes be disappointed on a scale from rarely to usually, depending on the tightness of your clenched asshole.”

Peter Greenaway has long been an arthouse staple, his background in painting evident in nearly every carefully considered frame. His cockeyed narratives (along with their ubiquity of actual cocks) have made him celebrated and divisive in equal measure, and Eisenstein in Guanajuato is arguably the British auteur at his most divisive, and definitely his most breathless.

The nice thing about unique and distinctive voices (or those voices that you know, from general hubbub, must be unique and distinctive), across mediums and across genres, is that when you finally get around to experiencing them, they very rarely are anything like you assumed.

A few highlights from our movie-watching week.

As Long As You’ve Got Your Health (1966)

Pierre Etaix was nearly left out of cinema history, thanks to a long-ago disastrous contract dispute, but has steadily clawed his way back from the margins — with some help from Criterion, not to mention the legions of fans and admirers who petitioned to end the decades of legal wrangling over his films’ distribution.