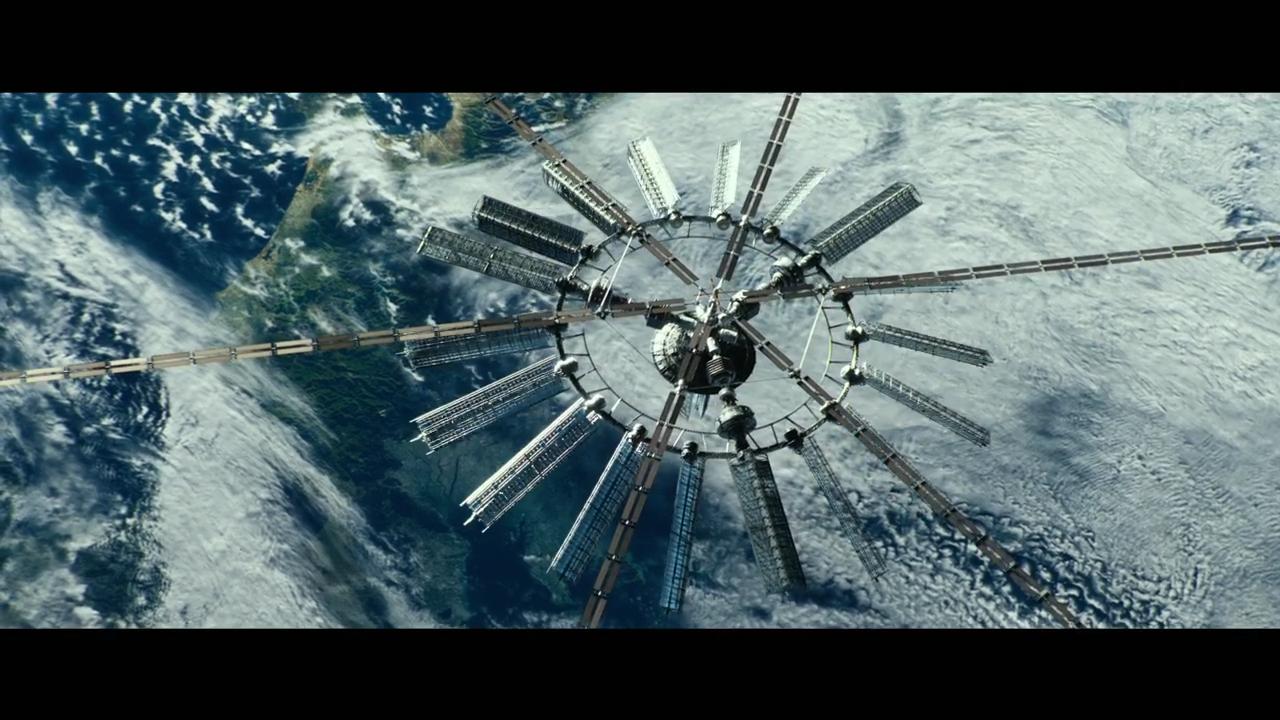

In Geostorm, there is an evil mastermind at work in the American government who has a plan to destroy the world with “extreme weather” via the wonderfully silly plot device of a satellite-based weather control system. The guilty party, the protagonists believe, is the President, but of course it isn’t.

February 2018

On several occasions in Eliza Hittman‘s shimmering, woozy Beach Rats, Frankie (Harris Dickinson) insists, “I don’t know what I like.”

It rings false — Beach Rats is a catalog of desires, a kind of aesthetic carnival of lazy afternoons near the water, glistening skin, boardwalk trysts, neon clubs (which reminded me of Hittman’s excellent 2011 short Forever’s Gonna Start Tonight), desperate fumblings between bodies in secluded spaces, fireworks — but there’s an element of truth to it.

It’s a platitude to say that emerging technologies inform our fiction. How couldn’t they? The raw material of everyday experience – our buildings, schools, livelihoods, family structures, routines, modes of communication – has always weaseled its way into cultural production, realist or speculative.

There are a lot of ways a filmmaker can be hard to like. They might make incredibly long films, or incredibly slow films, or incredibly slow, long films; they might be hard to track down, or hard to find in decent-looking formats; they might make wonderful films but be awful in real life.

How much sentimental Boomer Nostalgia does it take to turn a gripping historical moment into a chore? Steven Spielberg’s The Post, hurriedly rushing onto the pre-fab Oscar dais, asks and answers this question: exactly an hour and 56 minutes worth.

Don’t let the name or the opening moments trick you: Self-Criticism of a Bourgeois Dog is not really about dogs. But that feint is itself representative of Julian Radlmaier’s comedy, which propels itself along by sudden swerves.

Its first real narrative thread is inauspicious: Radlmaier, playing himself, out of money to make his next film, is forced to work at a peach-picking plantation, convinces a woman (Deragh Campbell) he is doing research for a new film that he wants her to star in.

With a quiet grace, and the kind of childlike innocence in its narration that lays bare the adult melancholy all around, Shin Sang-ok‘s My Mother and Her Guest (1961) sneaks up on you. It’s a far cry from the violent, Occupation-era love triangle of his A Flower In Hell (a previous Counter-Programming entry released just 3 years prior), though both star Choi Eun-hee.

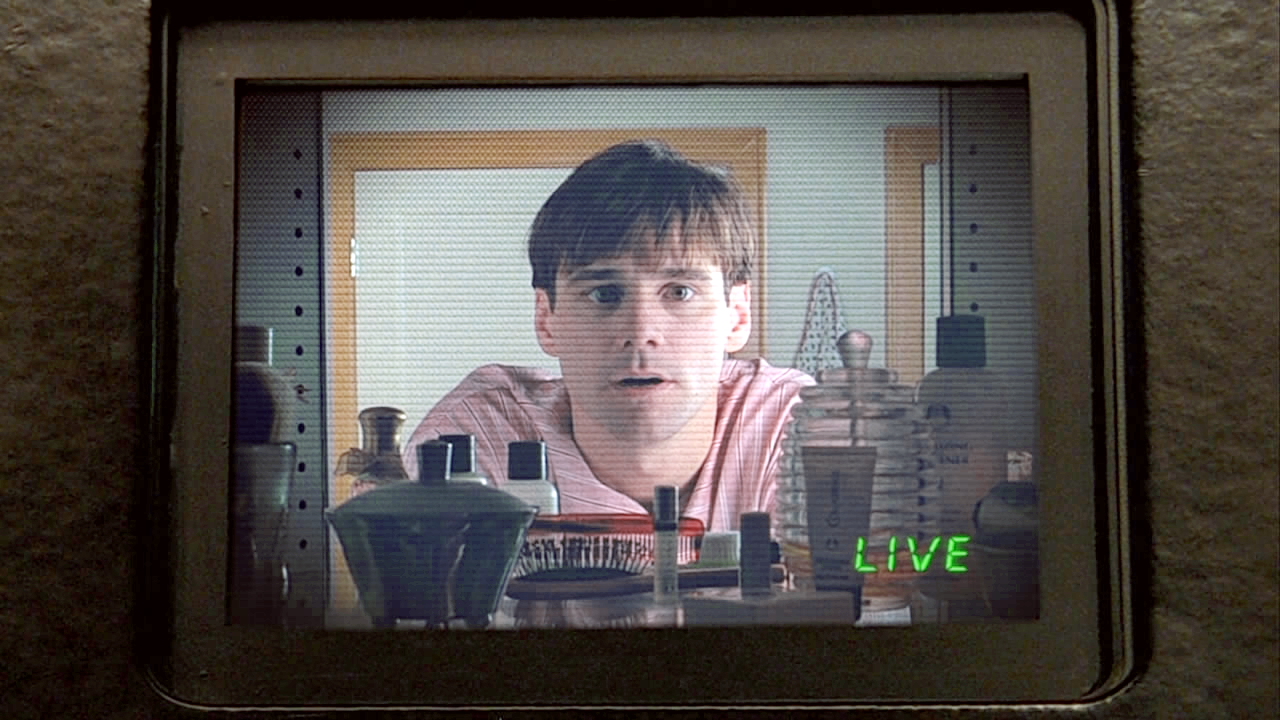

Skimming through Martin Buber’s two-volume collection of essays on the origins of Hasidism, I think I have realized what to call this loose category of fake world narratives, including The Truman Show: they are gnostic movies.

The idea of Gnosticism has been somewhat warped in the last 40 years (The Da Vinci Code, for example, has the audacity to claim they were suppressed for having a more human vision of Christ, when anyone with the least familiarity would tell you they had a far more divine version of Christ), but the basic premise is very close to these movies: that there is an evil god who has trapped human souls in bodies, and that the material world is, in fact, a massive prison to keep us controlled.

The lovable rogue is a cultural fixture. In his more thieving modes (he’s canonically male, usually stealing hearts along the way), he steals and redistributes or returns the goods for safekeeping (Robin Hood, Indiana Jones); steals because he operates best on the margins and needs to outrun an already dodgy past (Han Solo, Mal Reynolds, Jack Colton); or simply steals because it’s fun, he’s good at it, and it beats working for a living, like Monsieur Leval or, well, Mr.