The Coen Brothers’ filmography tends to swing wildly from lighthearted, goofball larks to existential nightmare tours of wounded psyches and uneasy human relations in a fallen world. (A good argument can, and has, been made that the two modes are in direct conversation.)

July 2016

In Taste of Cherry, Abbas Kiarostami’s 1997 Palme d’Or winner at Cannes, we almost never stop moving. It is a film about a man whose life has crept to a halt, filmed in ceaseless motion.

There is almost no way to talk about Taste of Cherry, about its most resonant aspects, without what our generation has termed “spoilers.”

Stories of childhood occupy a central place in our collective storytelling legacies. Like any art form, cinema has no shortage of entries: Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Kiarostami’s Where Is The Friend’s Home?, Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive, Spielberg’s E.T.

Battleship Potemkin and Sergei Eisenstein, its visionary creator and Soviet film theorist, loom so large over the history of cinema that there seems little left to say at this point. Treatises, books, films, encyclopedia entries have all been produced on the film’s tale of mutinous sailors and the triumph of the proletariat over murderous Czarist forces.

Laura Bispuri’s Sworn Virgin is, in her own a words, “a whole discourse on the body.” It’s an exploration of gender fluidity butting up against social norms as rigid as the mountains that surround its central Albanian village. In lyrical flourishes and with quiet, moving grace, Bispuri presents an unusually fraught journey to an authentic self.

There is a certain modest genius to a well-crafted disaster film. Unfussy and unpretentious, the best of these keep the proceedings simple, but their apparent simplicity can cloak the care with which plot details are placed and timed, the way individual moments correspond to each other.

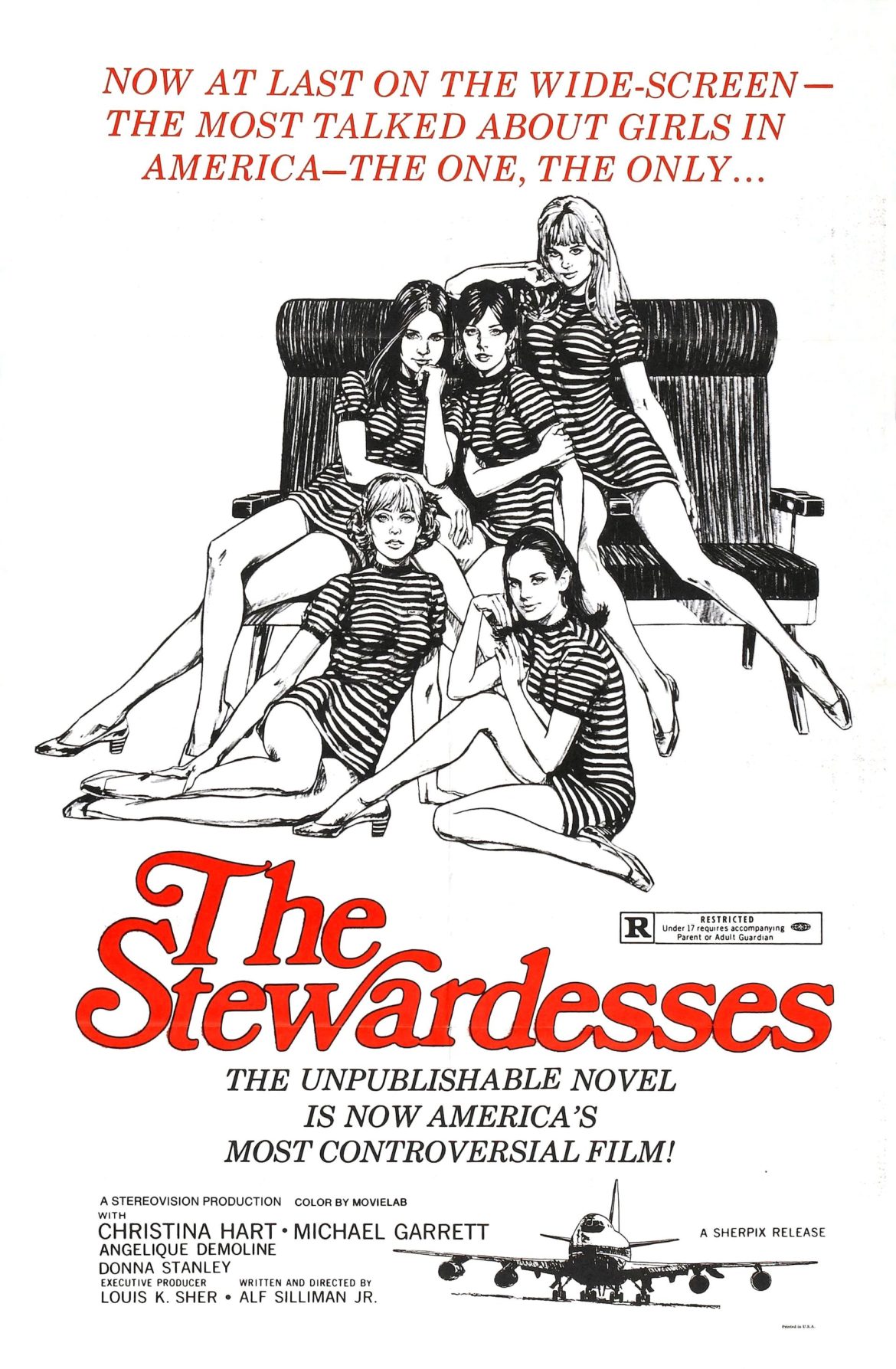

When Gaspar Noé released his excruciatingly boring porno cum arthouse provocation Love in 2015, a lot of ink was spilled about its central conceit: that the whole ponderous thing was shot in 3D, allowing Noé to figuratively spew bodily fluids in the audience’s face.

As Broadway’s longest running musical, “The Phantom of the Opera” tells a story of unrequited, impossible love and longing, set to soaring music and adored by legions of Andrew Lloyd Webber fans. What a surprise it is to discover, then, that its 1925 film incarnation, like the Gaston Leroux novel on which it is based, is a lot more like Saw.

The Week of The Dissolve soldiers on.

At this point, you may well wonder how much more I could possibly have to say. It’s not an unreasonable thing to wonder, but you may be surprised — I’ve actually been pretty moderate in my gushing praise so far.