By general agreement, 2016 was not the best.

The election of a know-nothing fascist clown to the U.S. presidency, ushering in what threatens to be a reactionary era of overt white supremacy while simultaneously placing his frightening clown-child-fingers next to nuclear-launch buttons? Not the best.

The deaths of a number of beloved pop-culture figures didn’t help matters, even if that seems likely only to increase, since beloved pop-culture figures tend to be kind of old and we’re paying more attention than usual. But, sure — not the best.

Small matters like the refugee crisis, epidemics of police brutality, the atrocities in Syria, the fact that climate change is probably past the point where we can reasonably counter it and we’re all going to drown or starve? Not terrific, much less the best.

Of course, many years have been not the best. 1347 was pretty bad, what with 50 million people dying of the plague. 1941 was pretty dark. The volcanic super-eruption in 72,000 B.C. wasn’t exactly a picnic, either.

In any case, 2016 was certainly not the worst year for movies ever. (That title goes to 2012, for the sole reason that it was the year Foodfight! was released.) Alongside all the serious business, the issue of whether a year was good or bad for film seems relatively frivolous – not that this has ever stopped anyone from speculating. And that speculation usually seems to land on the negative side of things. As a rule, anxieties about the death of a medium tend to run high in eras of technological change. And film sure seems to be on the verge of dying a lot.

Still, from where I’m sitting, 2016 was a pretty great year at the cinema. The best? No, probably not. But from horror-infused freak-out to small-scale storytelling, intimate documentary to absurdist farce, the past year delivered some gems. Here are 10 of those.

10. The Neon Demon

At this point, it is basically a truism that a new Nicholas Winding Refn film will feature prominently on both “Best of” and “Worst of” lists for the year. He’s that kind of filmmaker.

The Neon Demon lands solidly on this Best of. Sure, it’s nasty, meandering, stylish to a fault. But all of Winding Refn’s strengths are on full display, assuming you consider them strengths — lurid compositions, Argento-style splashes of color, and an extremely mean streak that fits the narrative. Elle Fanning sells the hell out of her cliched ingenue-in-L.A. role, a corn-fed beauty running headlong into the cannibalistic patriarchy of the world of modeling. (Special supporting shout-outs to the incomparable Jena Malone and an insidious turn from Keanu Reeves.) People talk here as though they’re in a movie — maybe not even a particularly good one — and Natasha Braier‘s cinematography entrances as much as it unsettles. (The fact that The Neon Demon was met with the usual charges of misogyny is somewhat hilarious given its overt narrative, but the fact that its DP and two of its three writers are all women makes it even stranger.)

This is also a funnier film than people seem to give it credit for. No matter. By the time the models are literally eating each other to further their place in the hierarchy, we are fully in Nicholas Winding Refn’s world. It’s deliriously gross, uncannily beautiful, and there’s nothing else quite like it.

9. The Fits

The breakout feature of the year — both for director Anna Rose Holmer and insta-star Royalty Hightower — The Fits is exceedingly difficult to summarize while adequately conveying its atmosphere and concerns. Let’s put it simply: here is a story about a tomboy somewhat alienated in school, a group of dancers she’s both enticed by and hesitant to join, and an unexplained outbreak of seizures that starts to infect all the girls.

Is there really an illness? Does it have to do with the water? Or is this an 80-minute metaphor for the pressures of conformity and Black femininity and adolescence? The latter seems strongest, but all options are on the table; in the age of shamefully ignored lead-poisoning (like in Flint, MI), the material explanations have resonance, too.

What’s extremely clear is the director’s sure touch (watch the many instances where key scenes are delivered through static shots of their observers rather than the action), the subtle and devastating lead performance from Hightower, and a climax that amazes even on second viewing. “Mood-piece” is no one’s favorite term, but it fits here (as it were). The Fits sustains an air of mystery and ambivalence for its whole running time, and it casts a spell.

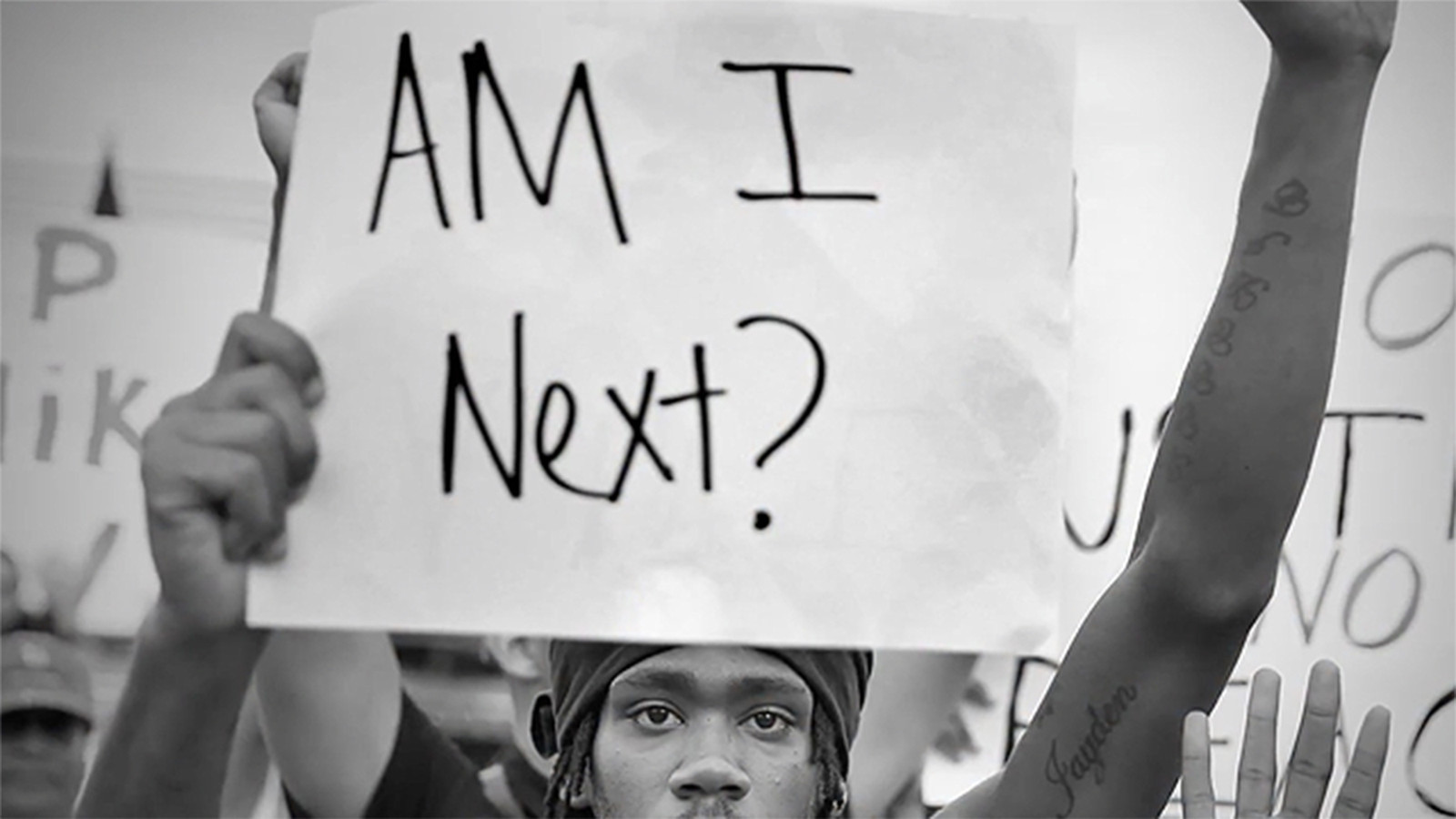

8. 13th

Earlier this week, I summed up Ava DuVernay’s masterful 13th for Cut Print Film’s best of 2016 list:

13th is a moral reckoning, an excavation of the image, and a call to action. Through its elegant staging and overlaid text, it entices the viewer to engagement. In this foul year, it’s compulsory viewing for anyone who wants to stare clear-eyed at the situation we’ve allowed to fester. And then get to fucking work.

I don’t have much more to add here. Watch it if you haven’t.

7. The Lobster

Loner Leader: Do you love her?

Campari Man: With all my heart

Loner Leader: How much do you love her? On a scale of 1 to 15.

Campari Man: 14.

It’s hard to imagine a drier, or odder, wit than that of Yorgos Lanthimos, and The Lobster is his wittiest, oddest outing to date. Its premise — a world in which coupledom is so rigorously enforced that those who fail to partner up are eventually forced to relinquish their humanity and be changed into animals of their own choosing — is weird enough. What’s weirder, though, is Lanthimos’ deadpan commitment to it.

There’s an aching melancholy to Colin Farrell’s central performance that serves as a ballast, rooting the absurdities of statist monogamy in a real-world loneliness, and Lanthimos is eager to mine both the humor and the pathos. Instead of ending up somewhere in between, The Lobster leaves the viewer on an entirely different plane, where mood, atmosphere, and characterization all work in different ways simultaneously. The film’s a tightrope walk, and it’s incredible they manage to pull it off at all. Like any tightrope walk, though, it’s ultimately thrilling, full of uneasy laughter and a disquieting sense that this world isn’t too different than ours, come to think of it.

6. The Shallows

Blake Lively is close to shore, 200 yards, but hunted by a shark. That’s it.

Everything else — the somewhat plodding back-story, the often gorgeous cinematography, the unnecessary final minutes that threaten to undo the film with sentiment no asked for or wanted … that’s all beside the point. The Shallows strips things down to the elemental, and delivers a white-knuckle genre film that entirely succeeds on its own terms. Sometimes, you just want to go to the movies and be entertained, and this was the most entertaining movie of the 2016 summer.

It also features a seagull as a central character, formally listed in the credits as “Sully ‘Steven’ Seagull'”. So points for that.

Jia Zhangke is mainland China’s foremost chronicler of the changing moment we find ourselves in, a sort of Abbas Kiarostami from Fenyang (and not just because he enjoys shooting inside vehicles). Mountains May Depart may not be his masterpiece, but it’s probably his most accessible film so far. And it’s beyond gorgeous.

A triptych that follows three characters through three eras (including the future, and shot in three separate aspect ratios to boot), Mountains May Depart is Jia’s rumination on history, globalization, and the things we lose along the way. Incorporating aspects of Hollywood melodrama and sly self-allusions, the film depicts a central love triangle over the years, the allure and danger of capital, and, in its wildly divisive third section, Jia’s concerns about the world to come.

It’s a heady mix of speculative fiction and grounded concern, anchored by his wife and muse Zhao Tao’s rapturous performance. There’s too much here, much too much, for a few paragraphs. Mountains May Depart is a film that stays with you — rigorously intelligent, aesthetically impeccable, and ever-shifting.

How do you make a film about the loss of sight and the emergence of a new mode of engagement with the world around you?

With grace and profound insight, Pete Middleton and James Spinney’s Notes on Blindness posits a few suggestions. Their film focuses on the British theologian John Hull, who spent years compiling an audio diary of just such a transition. The result is a film unlike any other released in 2016 — haunting, haunted, and hopeful by turn, it grapples with sound and image in ways that are both experimental and immediately familiar. Hull’s eloquent recordings are aligned with accomplished, lip-syncing actors, while the sound design (from Joakim Sundström, who’s also worked with Lars von Trier and on Berberian Sound Studio) fully immerses us in a world that isn’t so much opening or closing as it is transforming. We arrive at something like a cinema of blindness.

Our (sighted) assumptions may imagine this as a slog, a dirge for inevitable loss. Instead, the directors told me:

[John] concluded that, on the other side of a complex process of mourning, of trying desperately to compensate for the loss of these things, in the end they cease to matter. Because ‘being human is not seeing’, he said, ‘it’s loving’.

Notes on Blindness seeks to pay tribute to that love. To say it succeeds is a vast understatement. This is a masterpiece of humanism and grace.

3. La La Land

Ignore the critical disputes. Damien Chazelle’s follow-up to Whiplash improves mightily on that effort (indeed, how could it not?), crafting an ambivalent love letter to Cinemascope musicals while also firmly keeping its feet on the ground.

La La Land is not a movie about jazz or Hollywood, or even about our perceptions of jazz or Hollywood. It’s a movie about the collision of dreams and the workaday world that undermines them. It’s lovely and sad and funny, and neither Ryan Gosling or Emma Stone have ever been better.

In its final moments, before the technical wizardry of movie-magic allows us to indulge in some wish-fulfillment, Stone sings, “Here’s to the fools who dream / Crazy as they may seem.”

The emphasis is on “fools,” as it should be — a word that applies to their characters as much as the rest of us in the dark. Smile and wipe your tears away, and then head back into the world … a little sadder, a little wiser, and a little more entertained. What do we even go to movies for?

Kelly Reichardt is one of our most committed visionaries in film, focused, laser-like, on the moments other directors would leave out of the movie. A bare foot running along a lover’s back as he’s getting dressed, a pile of rocks outside an old man’s house, an awkward silence in a parking lot.

This is the stuff of drama in Certain Women, another triptych that starts nowhere, goes nowhere, and ends up in between. Based on the stories of Maile Meloy, Reichardt’s film is, unsurprisingly, at no pains to explain and in no hurry to get to the end. Its Montana setting shapes and encircles its characters, nearly all women, navigating the understated crises of their lives.

Only Reichardt could make this film, which understands that the most important things that happen in our days rarely involve explosions, of any kind. They involve routines, interactions at cross-purposes, internality in groups, the way the sky looks at particular moments, the dog who runs alongside us while doing chores, the effort to express something and the failure to get it across. We’re lucky to have her.

1. Moonlight

Well, the title of my original post about Moonlight probably killed any real surprise here.

Barry Jenkins’ film, an adaptation of the unproduced play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue”, startled me in the theater and hasn’t left my mind since. Awash in that titular blueness, it’s a visual marvel, but that’s only one of its accomplishments. Here is another film about the inexpressability of the things that most define us, all the more poignant because they are so elusive, so fragile, so dangerous.

Moonlight is about Blackness and queerness and the passage of time, in ways that open up insight without ditching specificity. This is, above all, not a film that can casually be said to touch on “the universality of the human condition,” or some similar phrase that manages to praise while also uncoupling its narrative from the world it depicts. This is a film about a life as it is lived, full of contradictions and pain and quiet joy.

Mahershala Ali shines in a supporting role; all three actors who play our hero at different stages of his life fully inhabit him. We sense where he came from and understand the how and why, but are left wondering where he’s going. Moonlight provides no easy answers. We simply find ourselves immersed in its images, like a young child encountering the ocean for the first time.

There will be Oscar-talk in the coming months, maybe outrage at slights. (Seriously, if Ali doesn’t get a nod, I’ll be there in person to burn the whole thing down.) But, as important as that kind of recognition can be, Moonlight already has changed the conversation. It stands as testament to a unique vision and a bracing honesty, carried on by a conviction in its truths that we rarely see. It’s a genuine cinematic event, and the best film of the year.