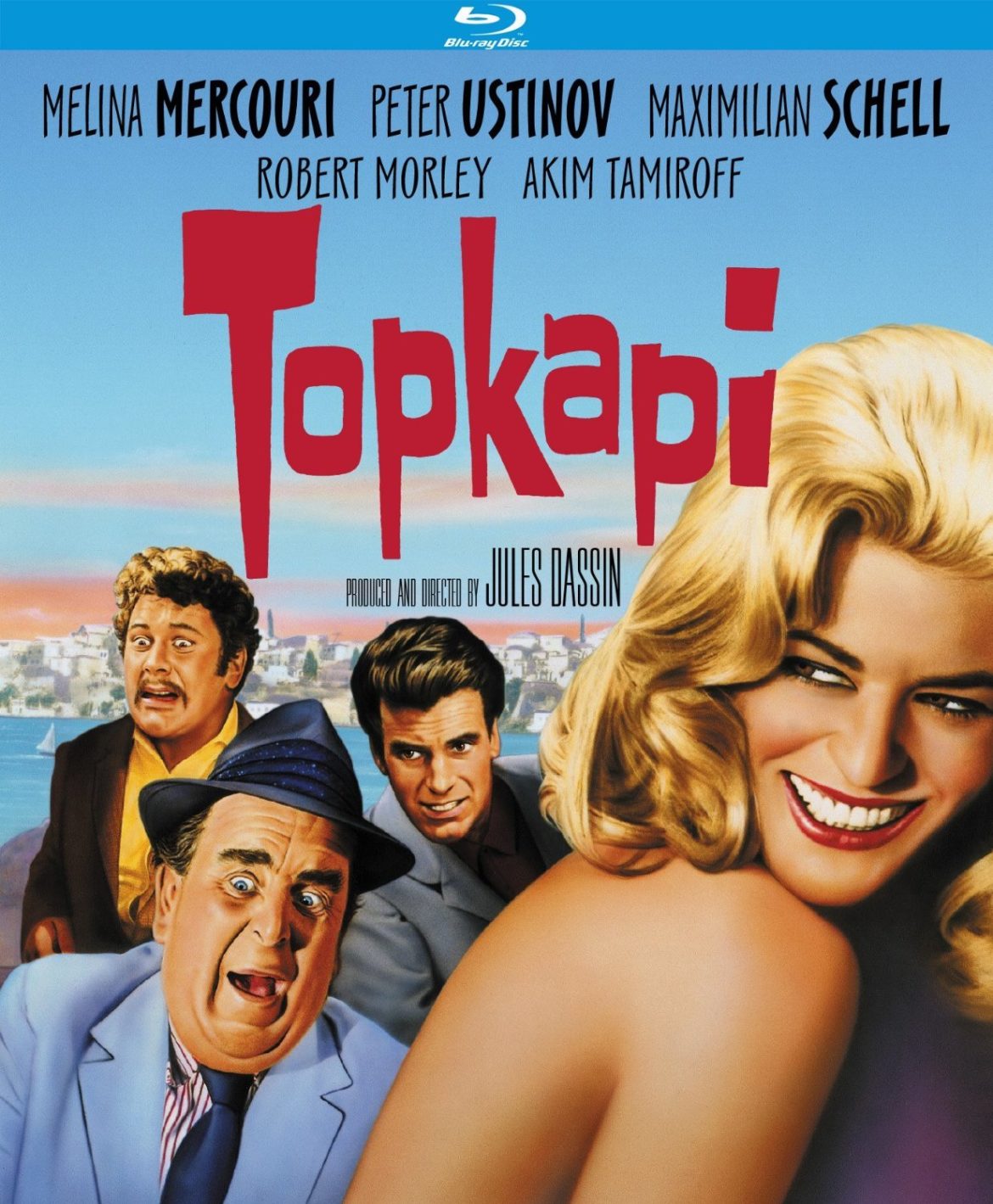

Quick! Free association game. I’ll go first: Maximilian Schell, Peter Ustinov, Melina Mercouri! Did you answer: Topkapi?

Probably not. (Though congrats if you did.)

These are huge names, but Topkapi is not. Between the three leads, they amassed 86 prestigious awards and nominations, including Oscars, Emmys, Grammys, Cannes triumphs, and whatever a CableACE award is. None of these recognitions, however, were associated with Topkapi, 1964’s 23rd top-grossing film. [Editor’s note: Ustinov actually did win an Oscar for Topkapi. I’m sorry if you lost at trivia in the brief moments this post has been live.]

This Jules Dassin-helmed, self-mocking Rififi knock-off starred all three, not to mention Marcel Marceau’s old mime buddy Gilles Ségal and archetypal curmudgeon Robert Morley. (Crime film veteran Akim Tamiroff gets prominent billing, though he’s barely on screen — a year later, he’d appear in Alphaville, so I imagine he didn’t mind.) Yet the film seems like a dream, a pre-psychedelic fantasia caught between noir and late ’60s farce — too colorful and goofy to be taken seriously and too committed to its weird obsessions and genre conventions to be read as farce. It’s an odd piece of business.

But a piece of business audiences loved in 1964, apparently. Critics were also kind: “It is another adroitly plotted crime film, played this time for guffaws, and if you don’t split something, either laughing or squirming in suspense, we’ll be surprised,” wrote the NYT’s Bosley Crowther, a critic it’s kind of hard to imagine guffawing, splitting things, laughing, squirming, or being surprised (though that use of the royal “we” seems about right).

Today, Dassin’s Rififi retains its place in the cinematic pantheon, while the mention of Topkapi seems more likely to induce blank stares than gushing praise. This can’t be entirely attributable to the fact that its title sounds, when enunciated, like a guy from Boston skeptically considering the first of the free weekly newspapers on the stack.

(Because it’s the “top copy”. C’mon, try it, ya schmo. Hey? Hey? Fine, never mind.)

In any case. Topkapi is a heist movie, like the film it affectionately sends up. Schell is Walter Harper, a dashing master thief, and Mercouri is Elizabeth Lipp, his sultry protégé who is also a nymphomaniac. (Mercouri’s lustful asides are, believe it or not, a highlight of the film.)

In any case. Topkapi is a heist movie, like the film it affectionately sends up. Schell is Walter Harper, a dashing master thief, and Mercouri is Elizabeth Lipp, his sultry protégé who is also a nymphomaniac. (Mercouri’s lustful asides are, believe it or not, a highlight of the film.)

The two haven’t seen each other in years, but reconnect when she’s hatched a plan to steal a particular emerald-encrusted sword from Istanbul’s Topkapi Museum. It’s one of several endearing touches in the film: neither anti-hero seems to need the money. Harper just likes a challenge, and Lipp, apparently, just really likes emeralds, presumably to wear when fucking. It’s the ’60s, man.

The twist? They will put together the usual crack team of criminals, but build it entirely of amateurs. This counter-intuitive conceit is explained away: they want to avoid people with long rap-sheets who might attract attention from the authorities. If you think about this for two minutes, you will realize it doesn’t make any sense, but the narrative chugs along at such a steady pace, and the frame is filled with so many colorful images, you are encouraged to cool it and just see how things play out.

The twist? They will put together the usual crack team of criminals, but build it entirely of amateurs. This counter-intuitive conceit is explained away: they want to avoid people with long rap-sheets who might attract attention from the authorities. If you think about this for two minutes, you will realize it doesn’t make any sense, but the narrative chugs along at such a steady pace, and the frame is filled with so many colorful images, you are encouraged to cool it and just see how things play out.

And so we meet the rest of the crew. Morley’s Cedric Page is an expert on eluding surveillance and alarms, the kind of guy whose house is equipped with self-closing blinds and wheeled mechanisms that bring you a drink when he presses a button. (Impressive, in the same year as Goldfinger? Not really. But cut the guy some slack, he’s trying.) Jess Hahn is, um, Hans, the muscle (as well as an implicit challenge to any future Forgotbuster-appreciation writer who would like to reference “Hahn’s Hans”.) Gilles Ségal is enormously irritating, and also a “Human Fly” called Giulio. If you expect that we will, at some point, see him climb walls and dangle precariously from things, you are not wrong.

All of which leaves us with Ustinov. His character is saddled with the name Arthur Simon Simpson: yes, he is British, in fact, and also, as we are repeatedly informed, “a schmo.” (There is a strong sense that the scriptwriters recently discovered the word “schmo” roughly three hours before shooting started and simply couldn’t stop repeating it. In fairness, it’s a terrific word.)

All of which leaves us with Ustinov. His character is saddled with the name Arthur Simon Simpson: yes, he is British, in fact, and also, as we are repeatedly informed, “a schmo.” (There is a strong sense that the scriptwriters recently discovered the word “schmo” roughly three hours before shooting started and simply couldn’t stop repeating it. In fairness, it’s a terrific word.)

Simpson is introduced at a Greek seaport trying to sell tourists bogus historical relics (like a schmo) and failing (like an even bigger schmo). Harper and Lipp make him their mark, and entice him to drive across the border to Turkey with their gear, including assorted weaponry (needed, we are reassured, for shooting out searchlights). Being a schmo, Simpson agrees, and – surprise! – gets promptly caught. This is one of the many easily foreseeable problems with intentionally employing amateurs and schmos for high-stakes international crime, but our protagonists are undeterred.

Rather than arresting him, the Turkish police forces enlist Simpson as a spy; given the cache of hidden weapons, they think, not unreasonably, that terrorism is afoot. Having no choice, Simpson agrees, but he’s eventually, and pretty comically, turned into an idiot double agent. Ustinov sells this frivolous narrative nonsense through sheer will and charm, channeling a sort of paunchy, doofus Peter Sellers, as he’s taken into the criminal fold.

Rather than arresting him, the Turkish police forces enlist Simpson as a spy; given the cache of hidden weapons, they think, not unreasonably, that terrorism is afoot. Having no choice, Simpson agrees, but he’s eventually, and pretty comically, turned into an idiot double agent. Ustinov sells this frivolous narrative nonsense through sheer will and charm, channeling a sort of paunchy, doofus Peter Sellers, as he’s taken into the criminal fold.

Eventually, we get to the heist itself. As in Rififi, it occupies a significant chunk of film time. Unlike in Rififi, it also involves a long segment where the entire crew attends a Turkish wrestling match at a coliseum, by way of distracting the authorities.

Dassin, who also directed the wrestling-themed Night and the City while on Blacklist exile a decade and a half prior, seems to be a fan. The sequence takes nearly as long as the heist itself, and its hilariously overt homoeroticism is weirdly contrasted with the lascivious enjoyment Mercouri finds in the spectacle. (It’s played for laughs, as Schell grows increasingly irritated with her lip-licking – Lipp-licking? – enthusiasm).

After we watch a whole lot of half-naked dudes grappling for an hour or two, the team manages to execute the heist. It’s a suitably tense affair: no one should doubt whether the guy who made Rififi knows how to ratchet up quiet tension. Ustinov’s Simpson, it turns out, also has vertigo, so that adds another wrinkle to the rooftop shenanigans. Palms are rendered appropriately sweaty as our protagonists and goofball stand-in hold taut ropes, delay searchlights, climb through high windows, and pull off their largely silly crime. But, in its closing moments, Topkapi reveals they didn’t plan for everything.

This is all pleasantly diverting, and it’s not hard to find its appeal. It’s a comedy, but there is just enough intrigue for audience members hoping for suspense, and just enough contrived sexiness for people who always hoped to see Peter Ustinov blush. But more generally, Dassin follows Hitchcock’s lead from To Catch A Thief: the location becomes the star, an exotic getaway the protagonists simply pass through for our amusement. Unlike Hitchcock’s oddly heist-free heist movie, Dassin at least does the audience the favor of showing people steal stuff.

This is all pleasantly diverting, and it’s not hard to find its appeal. It’s a comedy, but there is just enough intrigue for audience members hoping for suspense, and just enough contrived sexiness for people who always hoped to see Peter Ustinov blush. But more generally, Dassin follows Hitchcock’s lead from To Catch A Thief: the location becomes the star, an exotic getaway the protagonists simply pass through for our amusement. Unlike Hitchcock’s oddly heist-free heist movie, Dassin at least does the audience the favor of showing people steal stuff.

Filming for the first time in color, he seems swept away by its sensuous possibilities. Scenes are overloaded with an intoxicated rush that audiences must’ve found entrancing. Where Hitchcock buried night sequences in ominous, portentous greens, Dassin obstinately sets nearly all his shots in daylight, luxuriating in brightness and flash. Topkapi is a film about surfaces. In 1964, audiences seemed to respond.

Why, then, is the film remembered (if it is remembered at all) as something of a curiosity? At least part of it must have to do with the glut of wacky caper films of the 1960s, a trend Topkapi seems to both engage in and satirize. The earnest, straight-ahead heist movies modern cinephiles tend to admire — Rififi, of course, but earlier noir-tinged classics like Kubrick’s The Killing, Melville’s Bob Le Flambeur, Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra — had given way to much lighter fare, filled with hijinks and overstuffed casts, like It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, and location-emphasizing affairs, like The Italian Job. Not to say the grittier or more serious variety of heist film vanished entirely — it never will. But those originals will probably always be remembered more fondly than the wave of imitators and gentle parodies that appeared in their wake.

Topkapi is firmly in the latter camp, and is a lesser entry by any standard. It stands somewhere between the VistaVision spectacle of To Catch A Thief and the gang’s-all-here fun of Ocean’s Eleven, while managing to capture the magic of neither. In 1964, audiences may have been looking to the cinema for a vacation abroad and little else: a few laughs from more or less familiar faces, some naughty bits, an exciting centerpiece, and a suitable climax.

Topkapi is firmly in the latter camp, and is a lesser entry by any standard. It stands somewhere between the VistaVision spectacle of To Catch A Thief and the gang’s-all-here fun of Ocean’s Eleven, while managing to capture the magic of neither. In 1964, audiences may have been looking to the cinema for a vacation abroad and little else: a few laughs from more or less familiar faces, some naughty bits, an exciting centerpiece, and a suitable climax.

Topkapi still delivers all of those. But, like the museum you visited briefly two summers ago when traveling (presumably not to actually rob it yourself), you’ll likely only remember its most basic details.

This piece was written for The Solute, a contribution to a series celebrating Nathan Rabin’s Forgotbusters entries on the late, lamented Dissolve. Please read all of Rabin’s pieces! And check out The Week of the Dissolve here on this site, all week.