Yuan Muzhi’s Street Angel (1937), not to be confused with Frank Borzage’s silent of the same name from 9 years prior, is an odd assemblage of filmic impulses.

It’s often, for good reason, grouped together with films like The Goddess as part of the left-wing filmmaking movement of 1930s China, but it’s also a wacky sound picture filled with broad shenanigans, and also something of a musical. Two of its central songs – “The Wandering Songstress” and “The Song of Four Seasons” – are said to occupy something like the space Western audiences reserve for “As Time Goes By” or “Somewhere Over The Rainbow” … iconic, instantly familiar refrains that moved from cinema to the popular consciousness.

The politics are evident, but they seem to butt up against a more populist, Hollywood-spectacle sort of sensibility. Broad comedy gives way to melodrama, and back again, all underwritten by a palpable political outrage. It’s a strange film.

Muzhi opens with a montage of Shanghai street scenes, but before that, we get a glimpse of an imposing, “Western”-style building. The iconic lions of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) make an appearance, if we need help connecting the dots of inequality, and situating the film in the context of colonialism and Chinese post-Opium War subjugation to the British.

From the get-go, Muzhi emphasizes a city and a culture in transition, and sharply delineated worlds of haves and have-nots. The camera swoops from the moneyed heights down into the slums, and the implication is clear: these edifices are built on the backs of struggling people, suffering and singing and slapsticking their way through life as it’s lived down below. The film’s allegiances are announced.

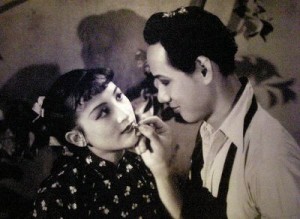

The narrative begins in earnest as we’re introduced to Xiao Chen (Dan Zhao), one of our key protagonists. He’s playing trumpet in a parade, while also cavorting with his newspaper-selling pal Lao Wang (Heling Wei) and trying to make eyes at Xiao Hong (popular singer of the time Xuan Zhou).

It’s a comical sequence – I mean, he trips over somebody’s feet, he blows copious amounts of spit through his trumpet like a big dork, and so forth – but the parade itself gives off an air of casual militarism. Muzhi may be poking fun at such displays, but there’s also a bit of a camraderie with the youth who find themselves in the middle of it. The clumsy marching trumpeter who really just wants to hang out with the girl is, in its way, a pretty familiar and charming figure.

The girl, Xiao Hong, is in a bad spot. Both she and her sister Xiao Yun (Huishen Zhou) are more or less indentured servants to abusive adoptive parents – Xiao Hong sings for pay in their bar, while her sister has been forced to work as a prostitute for extra money. Whereas The Goddess boldly posited its heroine as an unashamed sex worker making sacrifices for her family, Street Angel constructs a more coercive, angrier narrative – these are not women with agency, but exploited figures in a new class society, toiling anonymously in the shadow of Shanghai skyscrapers.

Yet Muzhi routinely interrupts the expected melodrama with out-and-out goofballery, like a stutterer who’d give Michael Palin’s Ken in A Fish Called Wanda a run for his money, and romance, in the desire between our trumpeter and singer, who sing songs of deep longing to each other. The kids go out drinking at one point, and we get some laughs at little fools who can’t hold their liquor.

But all this time, Xiao Hong’s sad prostitute lurks in the background, despised not only by her “parents” but by the gang of good-natured kids we mostly follow throughout the film. It’s interesting that Muzhi takes her character for his title – she haunts the comedy like a ghost, perched in the back of the frame reminding audiences that it’s not all fun and games.

Eventually, our “Singing Girl” (as the credits would have it) is to be sold off to a local gangster, and hijinks ensue as the team tries to spirit her away to safety (and true love). A shocking act of violence closes the story, tears are shed, and the camera pans back up a skyscraper. The effect is something like that of The Naked City – here is just one of the stories from the street, that the people in the new shiny buildings can’t see. There are, of course, many others.

A scholar on Chinese history could find many more resonances than I can. For instance, “The Four Seasons Song” contains lyrics evocative of rupture and split, and being pushed south of the Yangtze River – all of which are no doubt resonant and related to cultural touchstones. Most remarkable to me is the split between tones and moods, shifting from clear politically charged allegory to almost Marx Brothers-esque comedy to deep melodrama, and the interpolation of songs into the narrative.

Muzhi seems to have embraced the possibilities of sound films, casting a popular singer, commissioning songs that would become part of the fabric of Chinese cinema and cultural memory. (Here’s a fantastic version of “Song of the Four Seasons”, as performed by some wonderful random lady in 2007.)

In some ways, I’m reminded of Satyavit Ray’s The Music Room, another film that blended styles, spoke to changing norms and social relations in transition, and one that managed to be narrative cinema full of music rather than a musical.

The Goddess is, in my humble opinion, an outright masterpiece, but Street Angel shouldn’t suffer by comparison. There is a tremendous amount of ambition here, along with the lovely music. If the parts don’t fit completely in the end, it’s engaging from start to finish, and it’s not hard to see why it might be beloved. It aims to give audiences everything they might want from a film – romance, comedy, terror, outrage, melodrama, music – and it’s well worth a look.

Next up: God’s Step Children (Note: I skipped Let’s Go With Pancho Villa, since I can’t find a version with English subtitles and I don’t speak Spanish. Do you know where I can find one? Do you want to teach me how to speak Spanish? Lemme know!)