Before you dismiss this out of hand, consider the following. The Man Who Wasn’t There, probably their most underrated film, is essentially an adaptation of Albert Camus’ “The Stranger” (at least as much as A Serious Man is a retelling of The Book of Job). Fargo actively evokes notions of the Absurd, with Marge Gunderson’s final speech an almost paradigmatic example of existentialist reflection – “And it’s a beautiful day. Well, I just don’t understand it” – in fact, the critically-acclaimed TV series spinoff made this connection explicit by titling one of its episodes “The Myth of Sisyphus.” No Country For Old Men is a horrified vision of the confrontation between reason and the inexplicable. We could continue.

In any case, the release of Hail, Caesar!, generally received as a feather-weight complement to their more serious work, actually ends up reaffirming this. On the AV Club, Asher Gelzer-Govatos considers how it echoes Inside Llewyn Davis, arriving at a pretty convincing argument that the Coens make every movie twice – as, like Marx wrote, first tragedy, then farce. Focusing on theology, David Ehrlich thinks of it as the New Testament version of A Serious Man.

Hail, Caesar! could also easily be a companion piece to Barton Fink, two different but related tales of Hollywood. But following Ehrlich, I am going to compare it to A Serious Man, though instead of strictly theological implications, let’s talk some philosophy.

Since we have 3 rabbis in one film and an extended joke about the Christian Trinity in the other, here are 3 quotes from Camus, and some reflections on how the films echo each other and diverge.

“Man stands face to face with the irrational. He feels within him his longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.” ~ The Myth of Sisyphus

Camus’ philosophical lodestone, The Myth of Sisyphus is a short, dense summation of his way of looking at the world. Cursed to forever roll a stone up a mountain, only to see it fall back to the ground, Sisyphus is a tragic figure, the very image of the absurd. And yet, Camus insists, “one must imagine Sisyphus happy.” One must. In meeting absurdity head-on, and in embracing the likely futility of our efforts, the constant knowing that none of this matters and we must do it anyway, there’s a kind of freedom. Sisyphus’ happiness is an act of rebellion against the silence of the gods. Asking “why?” can never help – the only question is how to consider things.

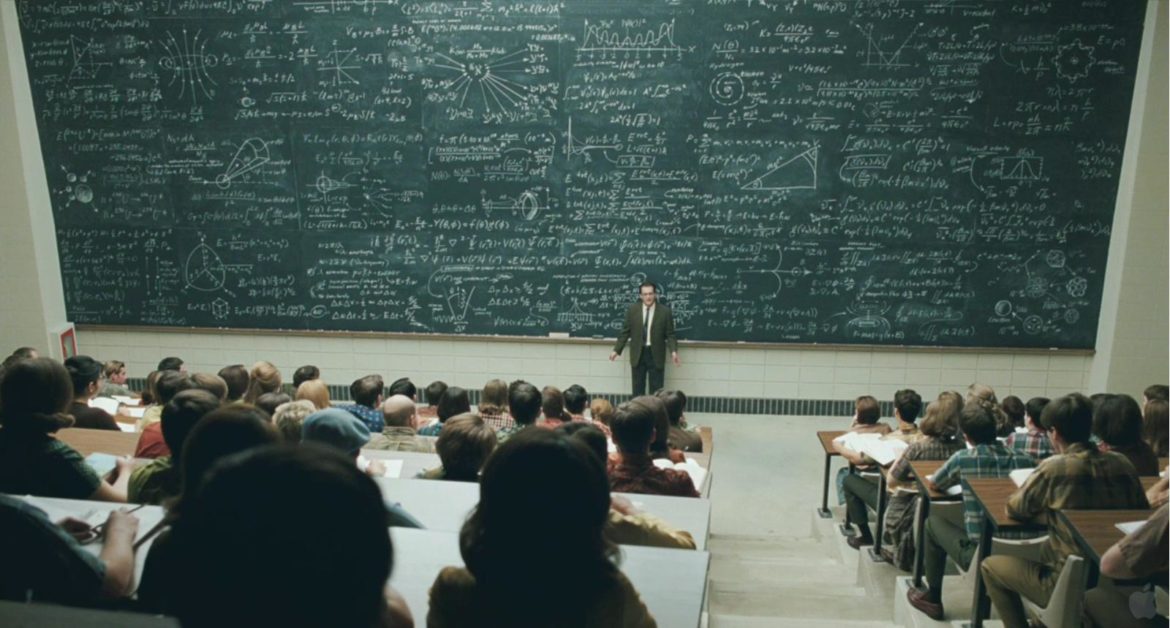

This is a point of view Larry Gopnik finds unacceptable. A Serious Man is, among other things, a study of the universe’s refusal to explain itself, and one man’s insistence that it must be explained. As a professor, he relies on mathematics and physics to detail the goings-on – there is always an equation. In fact, there are even equations that explain why some things can’t be explained (a joke Camus would’ve appreciated). But Gopnik’s problem – one of many – is this “confrontation.” As he asks Rabbi Nachtner, one of the three rabbis he consults, “Why does [Hashem] make us feel the questions if he’s not going to give us answers?” It’s a plaintive cry in the dark. Nachtner’s response? “He hasn’t told me.” This is, at root, the fundamental motivating idea behind Camus’ existentialism, and it animates the Coens films again and again. How do you live when nothing is there to instruct you if you’re doing it right? It’s a hard world for those hoping for guidance. We are on our own – free, and cursed with reason in an unreasonable place. Yet one must act. There’s no other choice, really.

In Hail, Caesar!, our protagonist Eddie Mannix is a Hollywood fixer tasked with keeping the engine of commerce humming. He’s beset on all sides by problems — a pregnant star who can’t fit into her mermaid outfit, a cowboy who has no place in the mannered drama the studio wants him to star in, a marquee star kidnapped by cut-rate communists. Things just seem to happen, and happen, and happen, and it’s Mannix’s job to keep the ship afloat. Conspiracies turn out to be mundane, grand plots are foiled not by intrepid sleuths but by the incompetence of the plotters. His search for meaning isn’t as agonized as Gopnik’s, but he’s still face to face with incongruity — the distance between meaning and reality. He goes to confession daily, but can’t find much to confess. He’s an important man in a silly world, and there are no signposts. Representatives from Lockheed want him on board, plying him with tiki drinks and impressive photos from the bomb site at the Bikini Atoll. What is any of this all about?

“If absolute truth belongs to anyone in this world, it certainly does not belong to the man or party that claims to possess it.” ~ “Socialism of the Gallows,” in Resistance, Rebellion, and Death.

There is no surer way to court catastrophe in a Coen Brothers film than to assume you have all the answers. What some critics have deemed their “smugness” or disdain for their characters is more often than not a rejection of individual arrogance, a sometimes gleeful, sometimes pointed take down of anyone who thinks they have it all figured out. The brothers’ absurd worlds can’t allow for the sin of pride, and the prideful end up with more than they bargained for.

In ASM, Larry Gopnik certainly can’t be faulted for claiming to possess absolute truth – quite the opposite. He’s adrift in the world, vainly searching for cosmic answers under circumstances that test his faith not just in G-d but meaning itself. Everyone else in the movie, though, appeals to higher powers and higher truths, and are routinely revealed to come up short. Profound insights amount to little – “The Tale of the Goy’s Teeth,” one of the film’s best sequences, maps this out as comic allegory; at the story’s end, Nachtner more or less shrugs off Larry’s sputtering desire for a moral. “We can’t understand everything,” he notes. “It sounds like you don’t understand anything,” Larry blusters. There is no absolute truth to be found, and anyone claiming it is a fool. The world offers no answers, because that’s not the way of the world.

In Hail, Caesar!, the critique of totalizing systems is played more broadly, without Larry’s tragic Old Testament subtexts. The Hollywood Communists are a collection of spiteful morons, and Whitlock’s “conversion” to their Cliff Notes version of Marxism hinges on the fact that he’s a moron, too. But the studio system the commies seek to undermine doesn’t fare that much better: Mannix holds the fictions together through fictions of his own, and even if the Coens are more sympathetic to the ephemeral beauty of make-believe than the hypocrisy of opportunistic Leftists, they don’t let anyone off the hook. Mannix’s daily trips to the confessional speak to his crisis of conscience, despite the fact that the worst thing he admits to is sneaking cigarettes even though he promised his wife he’d quit. The Church isn’t much help, the round table discussion between faith leaders about the depiction of the Trinity is played for laughs, and it all pales in comparison to the ludicrous but satisfying fantasies of The Christ that the studio puts on the screen.

“He who despairs of the human condition is a coward, but he who has hope for it is a fool.” ~ L’Hote

Contradictions inform all of Camus’ work. The very notion of the Absurd demands them, and the Coens share this throughout their filmography. This is a pretty resonant quote: its combination of cynicism and clear-eyed determination – do not despair, but keep your hope in check; marvel at the seriousness of the world, but laugh at anyone who would take it too seriously – is endlessly applicable. ASM and Hail, Caesar! both contain its echoes.

Larry Gopnik is in despair – why wouldn’t he be? A modern-day Job, bad shit just keeps piling up, and, as he keeps reminding us, he “didn’t do anything.” But his frequent protestations also underscore his passivity, and his cowardice: the double meaning is clear – he didn’t do anything to deserve this, but he also didn’t do anything at all.

He feels he’s entitled to answers, and discovers, over and over, that those answers will not be forthcoming. The root of his problems aren’t just grounded in the absurd, in Camus’ “confrontation between … human need and the unreasonable silence,” but in his coasting through life, his assumption that simply doing what has been asked of him is enough. After all, he has a good job, he’s up for tenure, he has a nice house in the suburbs for the family he rarely sees and doesn’t understand, he’s faithful to his wife, he’s more or less religiously observant. And yet, things are getting away from him, and he despairs. And, when good news finally arrives at the film’s end, it’s paired with cataclysms both personal (bad X-ray results) and apocalyptic (in the form of a literal tempest threatening to swallow everything). Despair always comes too early, and hope is a bad idea. Roll credits.

Passivity is not Eddie Mannix’s problem. In stark contrast to Gopnik, Mannix is the quintessential man of action – in fact, the guy the studio turns to when problems need fixing. The entirety of Hail, Caesar!is defined by movement, relentless and ridiculous, by Mannix’s decisions and refusal to give in to despair. But in his private moments, he’s torn – by doubt about his work’s value, whether any of it is worth the trouble. His daily trips to the confessional betray a man of action not quite sure he’s on the right path after all, and a “regular” job with war-mongerers holds a certain appeal. (Offers from the Devil often do.)

Does this make him an existentialist hero, insisting on the hopeless active over the despairing passive, direct engagement over ennui and fruitless searches for truths the world is unlikely to affirm? At no point is Mannix ever really hopeful or despairing, yet he’s still caught in a whirlwind of activity. He’s barely holding on, and the absurdity of his situation makes itself clear in every scene. He really is a serious man, but what he’s serious about is as close to total frivolousness as you can get. Still, the Coens seem to posit him as something like a hero – aware, and suffering, and duty-bound, without a trace of sentimentality, as he goes about the business of holding fictions together. Much of the film showcases the meaninglessness of those fictions, and we laugh right along.

Mannix has no time for laughter, or tears for that matter. There’s just the world and the responsibility to keep going. Hail, Caesar!‘s narrative evokes another famous Camus quote: “Where there is no hope, it is incumbent on us to invent it.” Amid all the zaniness, this could be the film’s more earnest subtitle – and where else do we find hope but in the movies?

“The invention of hope” through action, in a world of artifice, illusion, and unanswerable questions is about as existentialist as it gets, and a silly Coen Brothers comedy ends up mining unexpected depths.