Part of an ongoing effort to watch a set of films from non-White, non-U.S., non-male, and/or non-straight filmmakers and depart a little from the Western canon. The intro and full list can be found here.

The narrative of “The Dancing Girl of Izu” is apparently a familiar one in Japan.

From a short story by Yasunari Kawabata (the first Japanese person awarded a Nobel Prize, in 1968), it’s a simple tale: a university student goes on a trip to the country, falls in with a troupe of traveling musicians, develops a crush on one of the girls, and eventually has to go back home, melancholy to leave his new friends but energized by the adventure. It’s popular enough that Heinosuke Gosho’s 1933 silent is the first of six film versions. Not only that, but the story has penetrated daily life such that the express train from Tokyo to the Izu Peninsula is known as the Odoriko (“dancing girl”) in honor of Kawabata’s novel.

If you are anything like me, you did not know these things. This, it occurred to me, is partly why I started the Counter-Programming series in the first place. It is also why I had to watch The Dancing Girl of Izu twice.

I’m all for limiting “extra-textuals” and simply encountering a work of art on its own terms, but there’s “extratextual information” and then there’s basic context. For the first time in this series, it became clear how much nuance is lost if you simply don’t know the rich histories of the myths and stories some films draw on, particularly among silents.

Initially, I understood that this was the story of a summer vacation, a break from normal life, and perhaps a 1930s Japanese version of slumming it for the university student … weirdly, like a silent, Depression-era Almost Famous in reverse, except with many more inexplicable discussions about gold mines and blackmail for some reason. My second viewing was, unsurprisingly, far richer.

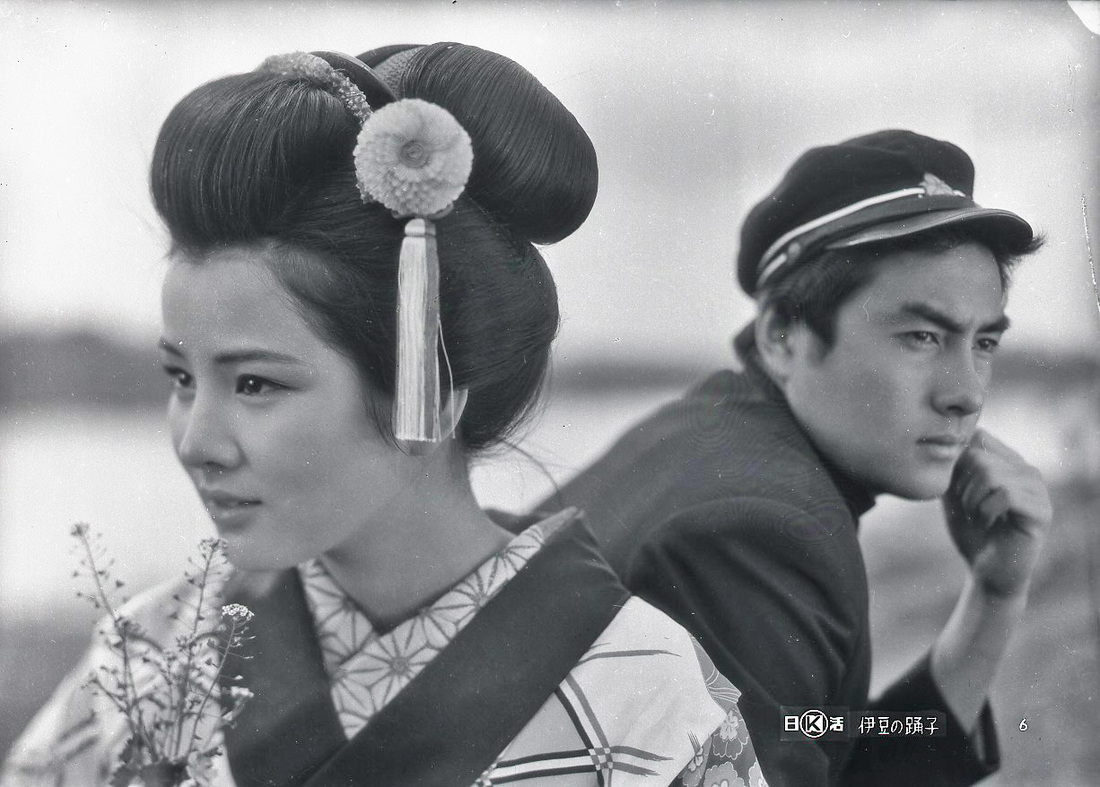

Starring the great Kinuyo Tanaka – who also appeared in Gosho’s The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine two years prior (Japan’s first “talkie”), not to mention memorable turns in some of the most esteemed films in cinema history, Japanese or otherwise, working with Mizoguchi, Ozu, and Kurosawa – Gosho’s The Dancing Girl of Izu starts with the basics of the story and works from there.

Kauro (Tanaka) is a dancer on the road with other traveling players, and Mizuhara (Den Obinata) is the university student who meets her on a walking tour of Izu. Through a series of plot contrivances, they end up spending several days together, and an ill-fated romance blooms. Ill-fated not because of some terrible tragedy, but in the way many summer loves are for young people – because they can’t last. Nearly the entire film is shot in daylight, an endless summer, with evocative shots of water that function similarly to those in Mario Peixote’s Limite, implying a tumult of emotion beneath the surface.

The film adds layers of melodrama and additional plotlines to the barebones narrative, and finds many moments of fleeting beauty and (arguably) some sociopolitical subtext. At its heart, though, it’s still the story Kawabata told, of brief, impossible love and young friendship, the search for beauty, and the eventual, inevitable parting of ways.

And also gold mines. Intriguingly, while Gosho was associated with the junbungaku movement — which “privileged fidelity to the original source … presented the story in linear fashion, ‘literally (and cinematically granted center stage, or center frame’ to the plot, and refrained from cutting or adding content to the narrative” (source) – he takes extensive liberties here. An entirely separate plot emerges about Kaoru’s brother having lost a gold mine due to his gambling, which is why they are now destitute traveling players. Increasingly complicated interactions result from this, including blackmail, which sometimes threaten to put the love story on hold while we resolve the issue of gold mine ownership. It’s kind of odd, but it does add at least a separate window into these lives, as well as evidence that Gosho was, perhaps, not as committed to the purity of film adaptation as making an interesting film.

Or maybe he just couldn’t resist widening the short story’s scope. Arthur Nolletti, in The Cinema of Gosho Heinosuke: Laughter Through Tears, associates this focus on money with the economic downturn in Japan at the time. That’s an appealing read, though an emphasis on social station and the uncrossable chasms between classes has characterized so much of Japanese cinema (including, apparently, nearly all of Gosho’s — this is my first). In any case, it’s hard to ignore so blatant an addition of theme, especially coming from a filmmaker at least on paper opposed to adding to the source material on principle.

In any case, gold mine shenanigans aside, the final feeling is one of sweet nostalgia coupled with sweeping melodrama – a series of tearful close-ups as the would-be couple parts is a highlight – and light comedy, as when two new friends swap hats and one admires his new look in a shop window. Gosho’s handle on the material is assured and obvious, and Tanaka is as expressive, charming, and heartbreaking here at 23 as she’d be in the ensuing decades.

As I mentioned at the start, one of the big revelations of watching The Dancing Girl of Izu, for me, was the awareness of how little I knew about the cultural context out of which it arose. This hasn’t been quite the case with this series until now. Even without background reading, I immediately get some of the resonances from Reiniger drawing on the stories of Aladdin or Cocteau on Orpheus. The first entry explored the links between Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates and what’s become something of a foundational myth itself, Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. But here was a film rich with nuance, and I just didn’t know the backstory at all.

I suppose I could view this as a fatal failing, and something that might invalidate me from writing hundreds of words about Gosho’s adaptation. Instead, it seems more like an opportunity. It’s not like I’ve gained some sort of cultural expertise by watching a single movie and reading some things on the internet, but I know slightly more, and recognize a few more connections, than I did previously. That’s reason enough to seek out something like The Dancing Girl of Izu, a lovely coming-of-story in its own right, filled with small moments of sadness and joy. These places we encounter in film, filled with new stories and old emotions, can make our own worlds at least a little bigger than they were before.

Next up: The Goddess, Yonggang Wu