Un Chant d’Amour is Jean Genet’s only film: a 26-minute, black-and-white, imagistic collage and fantasy of ideas. It’s startlingly beautiful, sensuous, and animated by themes — homosexuality, transgression, dominance, voyeurism — that characterize all of the mercurial artist’s work.

The short is also fairly, and hilariously, summed up by Letterboxd user Tyler, as “Almost definitely the best film ever made about gay men masturbating in prison.”

Frequently banned and famously litigated after an unauthorized attempted showing in Berkeley, CA in 1966, Un Chant d’Amour is arguably remembered now more for its notoriety than its content.

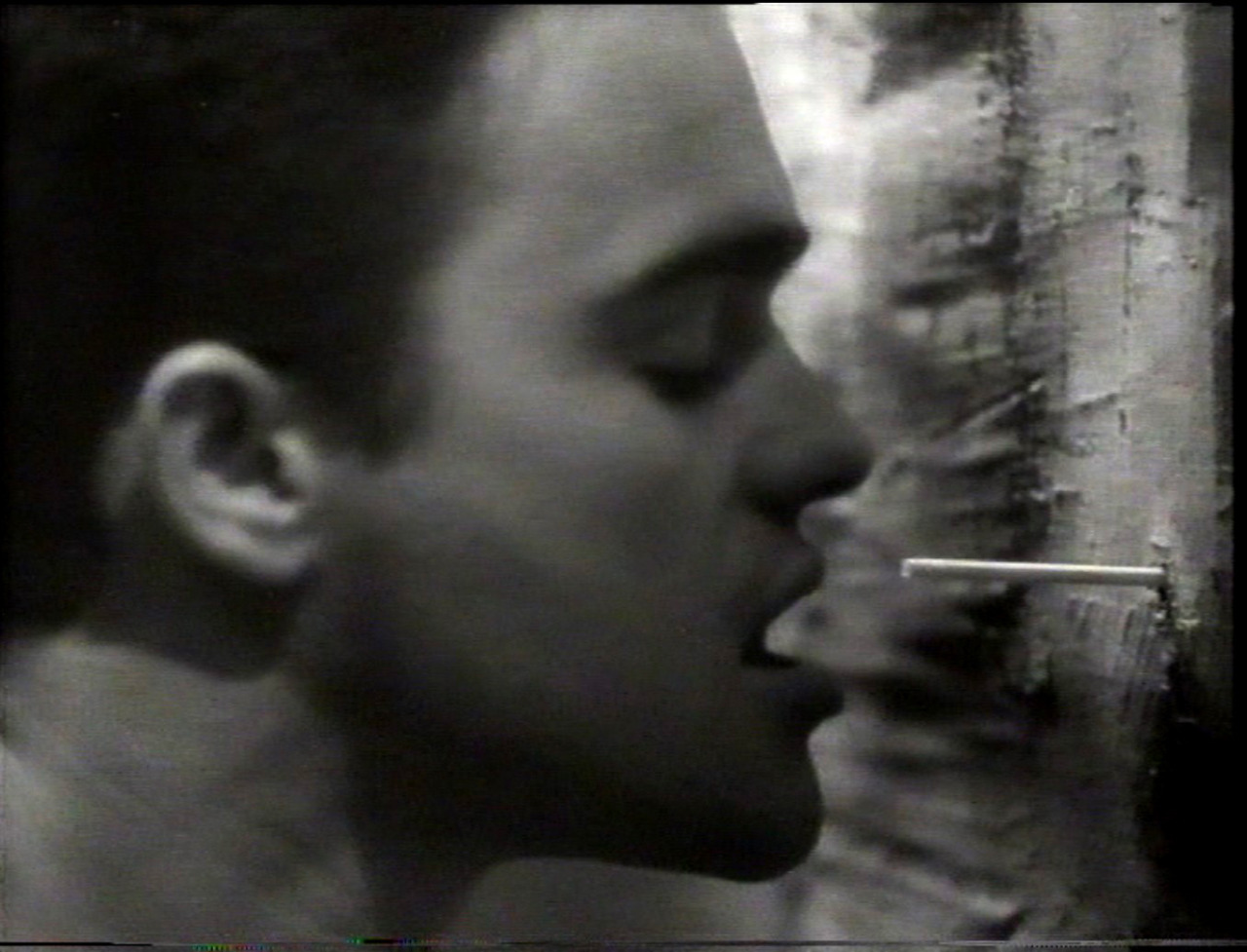

Like Cocteau’s “Orphic Trilogy”, Un Chant d’Amour is rooted in both film and dance. (Indeed, Cocteau is rumored to have shot the film itself.) It is, notably, a silent, in an era when that marked a definite aesthetic decision rather than a technical need. It focuses on an imprisoned man’s relationship with the man in his neighboring cell, and, it would seem, the jailer’s jealousy of their relationship.

For Genet, these things merge in a Surrealist fashion — a triad of dominance and submission in flux. It is never clear exactly who is in control: the nature of the relations seem to indicate a subversive reversal of expectation. It is the jailer who is shut out and the prisoners who are linked despite their walls. He eyes them through outsized cell windows, powerless to stop the lust he controls but cannot participate in. His entry into this congress comes via punishment: for instance, the use of his gun to demand allegorical fellatio.  Oh, gosh! That’s our Genet!

Oh, gosh! That’s our Genet!

There are other prisoners — notably a Black man who disrobes and masturbates, apparently embodying yet another variation of desire, gesture, and otherness — but it is these two we are drawn to. At one point, they make a break for the woods, and enjoy each other’s bodies there in ways the cells disallow. Of course, this is impossible, so we know we are in a fantasy realm. It is always up for debate whose fantasy we are experiencing.

Genet blurs the lines so effectively that Un Chant d’Amour becomes a set of reflections on desire rather than a narrative. The idea — clearly conveyed in exquisite photography that is indeed pornographic but so removed from the digital thrusting of our age that the word barely seems to apply — is that all of these images exist at once, in conversation. No one dreams alone. It’s scandalous in a fundamental way. As has often been the case, the censors were not wrong.

It’s a simple narrative, but its power lies in its evocations, invocations, and the montage-based contradictions the images introduce. There’s an extreme kind of seduction going on that mirrors that between the figures presented, a looming question of power and presence. Genet may have only made one film (though not for lack of trying), but it’s a heady mix of fear and desire. And, yes, also gay men masturbating.

And who was Jean Genet, the force behind the provocations of Un Chant d’Amour? An excellent question clouded by a lengthy history of self-mythologizing, answerable only through a mind-boggling resume of scandal, oppositional politics, and counter-cultural beatification.

Genet was an orphan, raised in a poor village in remote France by foster parents who eventually shipped him off to a penal colony for several years. Dishonorably thrown out of the Foreign Legion for extreme gayness, he reconstituted himself as a thief and prostitute, spending a fair amount of time in jail here and there.

His writing brought him to the attention of Cocteau, who he idolized and imitated, along with Picasso, Sartre (who wrote an entire book, “Saint Genet”, in his honor), and later Derrida. After May ’68, Genet became immersed in revolutionary politics, an outspoken proponent and ally of the Black Panthers in the U.S., the Baader-Meinhoff faction in Germany, and the Palestinian liberationists (he was in Beirut at the time of Sabra and Shatila, an experience that seems to have affected him deeply). He was the titular inspiration for David Bowie’s “The Jean Genie” and Glenn Milstead’s Divine in John Waters’ works, who took the name from one of Genet’s novels. Genet died an icon, controversial to the end, of liberationist struggles and groundbreakingly frank depictions of queerness. His legacy is long and weird, contradictory and subject to the kinds of routine re-inventions he himself seemed to treasure.

It’s tempting to apply some of these tendencies to Un Chant d’Amour, to decode it by way of the auteur. Throughout his art, he would return to images of wooded areas, as he does in the film. Do these evoke a nostalgia for his own provincial youth, re-routed through long-simmering desire? The peepholes and jailers could surely relate to his own imprisonments, punitive spaces where he ironically also discovered a truer sense of himself and his sexuality. The holy, sexy criminals that haunt the film, the mixture of pleasure and pain, the sensuality invented on the margins and in opposition … we could keep going.

Is Un Chant d’Amour, as the Alameda County Superior Court ruled in Landau v. Fording, simply “cheap pornography calculated to promote homosexuality, perversion and morbid sex practices”? Perhaps (though it certainly doesn’t look cheap). But I prefer to watch it as a fully realized expression in and of itself, a film in love with bodies, images, and the grace of the silents its creator grew up watching.

Pornography, to quote another famous case, is something one knows when one sees it. For Genet, obsessed with the eye in the doorway and bodies on display, seeing is always the point. And cinema, focused on gesture and figure and shadow, is ideal for this. As he wrote, with a characteristic eye toward scandal, “In effect the cinema is basically immodest. Let us use this faculty to enlarge gestures. The cinema can open a fly and search out its secrets…”

Un Chant d’Amour is just that – an opening of a fly. It’s deeply immodest and entrancing. It earned its notoriety.