For the near-entirety of its 80 minute running time, Blue Jay is a resolutely understated affair, more interested in partially-concealed longing and lingering, unspoken hurt than emotional fireworks.

Alex Lehman‘s character study comes pretty close to blowing this tone in its final moments, as we’re treated to outbursts we didn’t ask for and the film doesn’t need, but up until that point, it’s a lovely portrait of two people navigating their shared pasts and conflicted presents. Mark Duplass and Sarah Paulson both turn in remarkably nuanced performances, investing Blue Jay with warmth and emotional weight.

This is a very good thing, since, with the brief exception of veteran character actor and one-time Western star Clu Gulager, their Jim and Amanda have the only lines in the film. Blue Jay seems to take place in a world where every other competing force has dropped out, leaving just these two people and their memories.

Jim and Amanda were high school sweethearts who drifted apart over the years. They run into each other at a grocery in their hometown, performing an awkward dance as they recognize each other and gauge the situation to see if they should even interact. We get the sense that there’s some sort of trauma that underlined their split, and Duplass especially sells Jim’s hesitation and embarrassment.

Of course, they clear this hurdle and end up spending the day together. (Good thing, or there’d be no film.) They visit old stomping grounds, like the titular Blue Jay Cafe, buy beer from the same store they used to haunt as teens, and listen to silly old recordings they made at Jim’s mom’s house, which he’s now renovating since her passing. Things are wistful and halting, in ways familiar to anyone who has loved and lost. Which is to say nearly everyone.

Paulson puts on an acting showcase, and the ubiquitous Duplass (who also wrote the screenplay) gets some room to breathe outside of his standard mumblecore motions. The essential staginess of Blue Jay‘s set-up is undercut by its black and white cinematography, sense of place, and reaction shots. Moments that could be maudlin — a dance sequence set to Annie Lennox’s “No More I Love You’s”, for instance, or an impromptu role-play of the happy bourgeois couple they once imagined they’d inevitably become — end up working in spite of themselves. Other, quieter ones — like the look on Paulson’s face when Duplass saves her the pink jellybeans in the bag (“Your favorites,” he shrugs) — land with surprising intensity.

These are entirely believable people whose greatest joys and sorrows are inextricably linked to places, people, and connections decades gone. They’ve moved on because they’ve had to — bad choices, unsent letters, things left silent that should’ve been voiced. Blue Jay is a slight film about the big issues that came to define us before we even knew who we were. Its third-act missteps are forgivable in context, if only because its leads are so strong. Here, as ever, you can’t go home again, and this awareness haunts its characters’ every smile. You might find a lot of yourself in Blue Jay‘s silences.

Quick Links

Like her Greek filmmaking compatriot Yorgos Lanthimos, whose Dogtooth and The Alps she produced, Athina Rachel Tsangari likes skewed takes, awkward silences, and mining discomfort for black comedy. These sensibilities are all on display in Chevalier, an attack on competitive masculinity and group-think that is never quite as bracing as it means to be but remains worth watching all the same.

On a fishing boat, a group of friends find themselves competing with each other in matters large and small. Eventually, they hit upon a great idea: determining who is “The Best, In General”. Let the games begin. Chevalier grapples with many ideas, and finds bleak, escalating humor in these macho competitors’ absurd self-satisfaction and mercenary will to win. If the whole thing ends with more of a whimper than a bang, and suffers by unfair comparison to Lanthimos’ 2016 masterpiece The Lobster, at least it’s a fun ride.

Mike Flanagan’s films do not necessarily inspire confidence immediately. But Oculus, about a death mirror that kills you with death, was a surprisingly strong horror entry in 2013, and his Ouija: Origin of Evil (which I haven’t seen yet) got even more surprisingly strong reviews, at least insofar as it’s a film called Ouija: Origin of Evil.

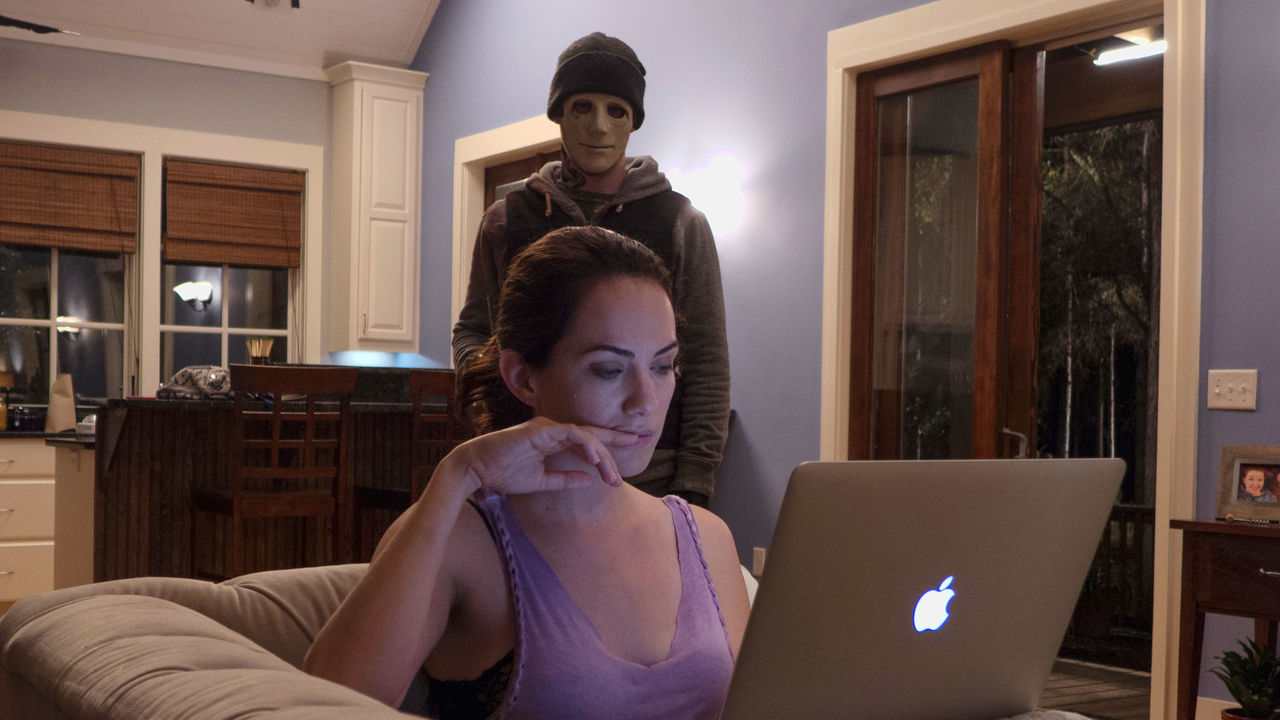

Hush might make a trifecta. This is no groundbreaking cinematic experience, but it is an entirely solid, effective home invasion thriller, complete with a compelling twist and a strong performance from lead (and co-writer) Kate Siegel.

I’ve long maintained that there is little scarier than suddenly seeing a face you didn’t know was there through a window. Hush agrees with me, pairing that face with our deaf protagonist’s dread and apparent powerlessness. There are jump-scares and a bit of gore, but the strength of the film is elemental. A shadow, a guy peering in, a silence. Scary enough for me.

If this year’s Everybody Wants Some!! — Richard Linklater‘s affectionate ode to bros, bongs, and college baseball — felt slight, that might just be because it came on the heels of Boyhood, the purest single-film distillation of his tone and approach. Famously shot over the course of 12 years with the same cast, Linklater’s Texan opus caused a stir on its release, generating swooning praise and a fair amount of backlash.

Now that the hoopla has died down, maybe we can appreciate Boyhood for what it is: a monumental commitment to a single narrative, lovingly rendered by our most American auteur.

Another entry in this Netflix column that is not, in fact, on Netflix, D.W. Griffith‘s 1912 short is often hailed as the first gangster movie, and it’s now available to watch in streaming HD from the Museum of Modern Art.

It’s fairly remarkable to revisit it over a century later. Featuring as many social realist touches as gunfights, with Lillian Gish an obvious star-in-the-making, the 15-minute spectacle also stood at a crossroads, as MoMA notes:

Rich in plot, characterization and social observation, Musketeers pushes the limit of the one-reel format of early cinema, looking forward to the feature-length films that would conquer the industry one year later.

This is the first film from MoMA’s collection of restorations to be released in this format, with others to follow. For anyone fascinated by cinema history (or gangster movies, for that matter), that’s cause for celebration.