The tagline for The Big Heat —“A hard cop and a safe dame!”—is, to quote Otto, “flagrant false advertising.”

Combined with the poster, it promises a classic noir clash between a sultry dame and a hard-boiled detective. In reality, the two of them (Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame) barely share three scenes with one another. And there’s never any chance of them falling in love: Glenn Ford is far too in love with this dead wife (Jocelyn Brando, Marlon’s incredibly talented sister who should have been far more popular than she was), whose murder he spends most of the film revenging.

But in another sense, it’s actually very accurate. The women in The Big Heat are soft—literally. Their bodies are recipients of force, and they bear its marks.

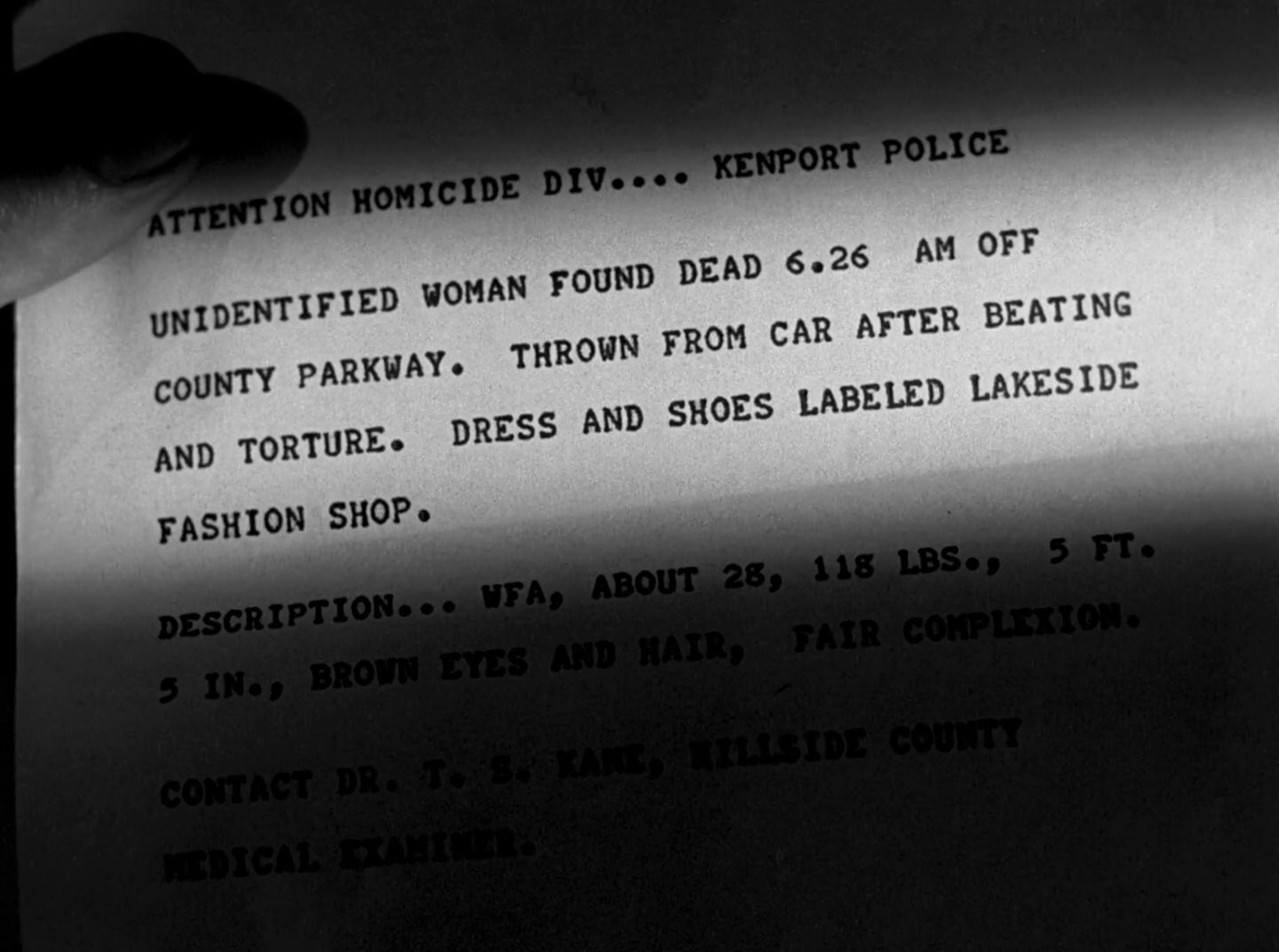

All four of the significant women characters die before the end of the film. The mistress of the cop whose suicide kicks off the film is murdered off-screen, tortured with cigarette burns and thrown into a river; the explicit description of it as “torture” is uniquely explicit for the 1950s. Glenn’s wife is blown up by a car bomb meant for him just barely off-screen—we see the brightness from the explosion and the wreckage afterwards.

Gloria Grahame’s mob moll has her face burned off by Lee Marvin and a pot of boiling coffee, leaving her with Harvey Dent-level scars down the side of her face. Finally, the dead cop’s widow is shot dead, getting off fairly easily and merely slumping to the floor.

Gloria Grahame’s mob moll has her face burned off by Lee Marvin and a pot of boiling coffee, leaving her with Harvey Dent-level scars down the side of her face. Finally, the dead cop’s widow is shot dead, getting off fairly easily and merely slumping to the floor.

It’s incredible the amount of violence that women receive. Even those who barely appear don’t come out unscathed: one scene has Marvin burn a random woman with a cigarette.

This is paired with a surprising lack of violence against the men of The Big Heat. They make out pretty well, with one exception at the climax, when Grahame gets her coffee-based revenge, scarring Marvin’s face. (Although, it’s Lee Marvin, so it’s not exactly a major loss.) All the bad guys are indicted off-screen, and we’re informed via the classic spinning paper. How do we square this distribution of labor?

It might have something to do with how un-mysterious this movie is. It’s basically never a secret who is behind the suicide that puts everything in place: Alexander Scourby’s “Lagana”, an easy stand-in for all corruption and authority. Ford goes through the signs of investigation, but even at the end when he figures out who planted the bomb in his car that killed his wife, no progress is made.

It’s more accurate to describe the first 80 minutes of this 90-minute movie as slowly increasing intensities. More than any unraveling of clues, every character just stands around and becomes more and more motivated, more and more hateful, more and more energetic. Within their bodies, motivation builds and builds and builds until it explodes.

And how can these mostly male bodies express their building amounts of energy? Only by expressing their force on the soft bodies of women, whose separation from the world of power politics makes them purely objects. The cigarette burns, the explosion, the horrific scars: they are signs of force, of narrative force, acted out permanently.

The Big Heat then might be something like a noir about noirs, or a noir without a skeleton. In short, among mainstream 1950s noirs, it’s completely unique, and well worth watching.