This could serve as both mission statement and post mortem for Cannon Films, the now-legendary purveyor of factory-generated bottom-of-the-barrel schlock and occasional arthouse masterpieces. It also neatly encapsulates Golan’s mixture of candor, pride, and total disinterest in anything but movie-making. Electric Boogaloo is an affectionate, and affecting, portrait of Golan and Cannon, and essential viewing for anyone who grew up watching movies on TV in the 1980s.

“But we made films.” Did they ever.

From its inception in 1967 until it was acquired (for $500,000) by Golan and his cousin Yoram Globus in 1979, the company produced about 40 films – ranging from tripped-out late 60s fantasias like Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Fando and Lis to the violent, reactionary anti-counter-culture hit Joe, and eventually settling into the Happy Hooker series and films with such dubious titles as The Yum Yum Girls and Cheerleaders Beach Party. Soft-core skin flicks made money, but not enough. The Golan-Globus group, already boasting the biggest box office success in Israeli history (Lemon Popsicle), were desperate to break into the U.S. market.

The result? Cannon cranked out nearly 200 movies in the following 17 years, including at least 28 in 1987 alone. (By way of comparison, Warners produced 18 that year, if you generously include its co-productions with companies like Cannon.)

Brash, generally disreputable, often lacking narrative coherence, full of nudity and violence and muscles and questionable fashion choices and breakdancing, Cannon’s films are synonymous with the 80s. Even if you aren’t a bad movie connoisseur, you probably know some of the titles. These were the staples of many a young film fan’s diet during the decade: Death Wishes 2 and 3 and 4, all of the Chuck Norris vehicles like the Missing in Action series and Delta Force, King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quartermain and the Lost City of Gold (both starring a young Sharon Stone, cast because Golan demanded “that Stone woman,” meaning Kathleen Turner from Romancing The Stone … oh well, let’s just go with it), Cobra, Superman IV, Bloodsport and Kickboxer and Cyborg.

Brash, generally disreputable, often lacking narrative coherence, full of nudity and violence and muscles and questionable fashion choices and breakdancing, Cannon’s films are synonymous with the 80s. Even if you aren’t a bad movie connoisseur, you probably know some of the titles. These were the staples of many a young film fan’s diet during the decade: Death Wishes 2 and 3 and 4, all of the Chuck Norris vehicles like the Missing in Action series and Delta Force, King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quartermain and the Lost City of Gold (both starring a young Sharon Stone, cast because Golan demanded “that Stone woman,” meaning Kathleen Turner from Romancing The Stone … oh well, let’s just go with it), Cobra, Superman IV, Bloodsport and Kickboxer and Cyborg.

Cannon was deeply schizophrenic in its choices. Its first legitimate hit was Breakin’, an actual, honest-to-God watershed moment in hip-hop and breakdancing history that the cousins just stumbled into … and then promptly shit the bed with their quick-release, cash-in sequel, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, a title the internet has latched onto to denote anything ridiculous and shark-jumping.

For every record paycheck made out to a Sylvester Stallone for things like the ill-fated arm-wrestling saga Over The Top, there was an art film like John Cassavetes’ swansong Love Streams (two films we’ll look at later this week). The company green-lit Tobe Hooper’s gonzo-comic sequel to Texas Chainsaw Massacre, starring a deeply unhinged Dennis Hopper, while also funding Franco Zeffirelli’s alarmingly beautiful adaptation of Otello. Golan wrote up a contract on an actual napkin and signed Jean-Luc Godard, the auteur’s auteur, to direct an avant-garde King Lear with Norman Mailer, while still generating movie after movie about improbably American ninjas and the Dolph Lundgren-focused Masters of the Universe live-action He-Man story, a comic action film aimed at kids and adults, and roundly rejected by both. It was, by all accounts, a weird ride.

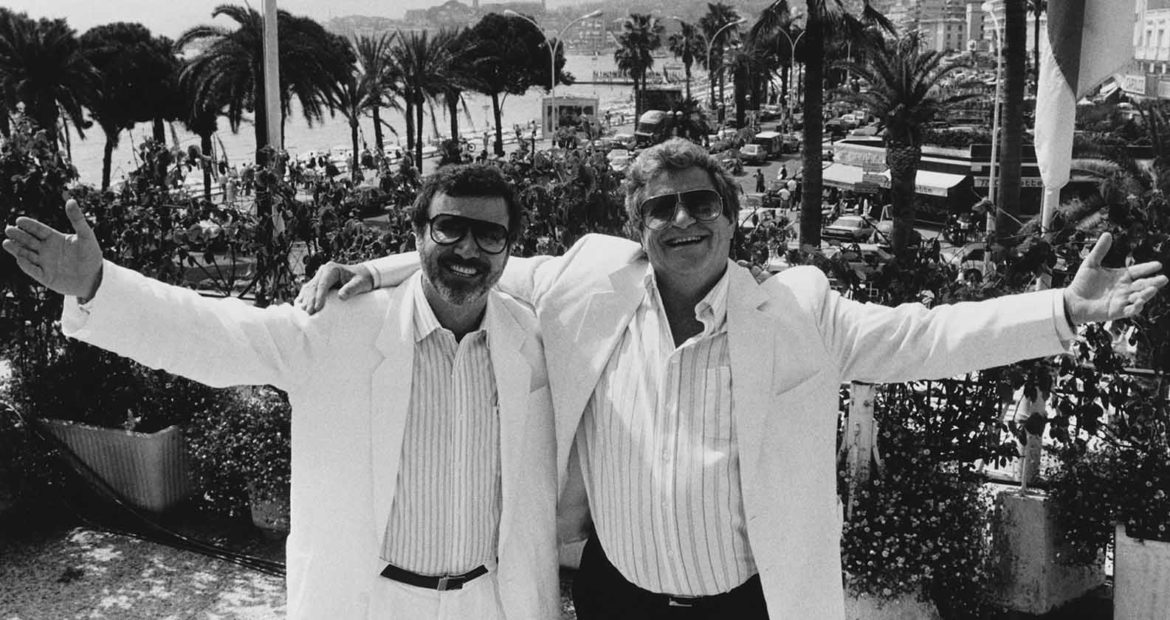

Electric Boogaloo (the documentary, not the good-will-wasting sequel from 1984) charts this weirdness, the rise and fall of a company drunk on its on cinematic enthusiasm. It’s very funny, but also poignant. Golan and Globus were outsiders through and through – as Israelis who had succeeded in their home country’s film industry through sheer will and relentless self-promotion, they were not the sort of folks who were going to tone it down for the U.S. market, and they were treated as interlopers and, maybe, charlatans. (There’s more than a hint of barely coded anti-Semitism to some of their enemies’ pronouncements – “The Bad News Jews” was a moniker that got tossed around, alongside The Go Go Boys and many others.)

Their business model – sell a film on its poster, collect pre-sales, get the movie made on the cheap, kick it out the door, use the funds to finance the next one, slip in some money for prestige art pictures, repeat – wasn’t ever going to be sustainable, and of course it all came crashing down. But holy shit, what a run. And Cannon basically invented the entire notion of “pre-sales,” which now structure the industry and are taken as commonplace. The real problems, as many people in the documentary point out, arose when the cousins strayed from this model, taking on big-budget projects like Superman IV and Over The Top, which they didn’t have the money to do right by … or in the latter case, probably shouldn’t have done in the first place. But who knows? Maybe, if the stars had aligned slightly differently, we’d have seen an explosion of arm-wrestling movies. It’s not likely, but it’s not impossible.

Golan and Globus eventually split – the insane and out-of-touch nature of the split exemplified by their mad, competing rush to beat each other back to their earliest success with Breakin’ by being the first to release a lambada movie, glorifying a dance craze that never existed and never will. Golan’s limping remnant of Cannon put out Lambada, while Globus countered with The Forbidden Dance (Is Lambada), under the rubric of his newly founded, and slightly suspicious sounding, “21st Century Film Corporation.” Appropriately and ridiculously enough, the two films were released on the same day. The public did not take sides, opting instead to laugh at the pre-fab oddness of competing lambada movies. They died quiet, presumably sexy deaths.

It’s a poignant, sublimely absurd coda to an often exuberant, sublimely absurd story, but so it goes. Electric Boogaloo does an excellent job conveying the manic, arguably misguided passion behind the Cannon saga, though, and it’s hard not to salute Menahem Golan by the end. (Movie-mad Golan overshadows business-man Yoram Globus in every way here.) There’s something eternally 10-years-old in Golan’s approach, his childlike excitement to have anything to do with making movies … though perhaps that’s just my own 10-year-old self speaking, a little moron in front of a VHS player who considered Bloodsport an unqualified masterpiece.

At its heart, the Cannon story is really about the highs and lows of cinephiliac passion, about the questionable choices people make when they refuse to pause and consider what they’re doing. On the other hand, as Golan says so eloquently and inarguably: “we made movies.” Good, bad, indifferent. Borderline pornography or arthouse triumphs that never made their money back, but are now held dear by fans across the world. “We made movies.” Yeah, they did.

In any case, nothing’s ever totally finished. Upon catching wind of Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films, the cousins refused participation with the project and instead reunited to produce their own self-documentary, The Go Go Boys: The Inside Story of Cannon Films. You can almost hear Menahem Golan shouting, “If anyone’s going to produce this fucking movie, it’s going to be us!” And so they did.

The cousins’ film, the producers of Electric Boogaloo wryly note in its closing frame, made it to the screen several months ahead of their own.